From an early age, I was brought (unwillingly) to Chinese school every Sunday morning, a class that I dreaded throughout the week. I would put off my homework until Saturday night and struggle to memorize the characters that I needed to know for the next day. Even for the final exam at the end of the year, I would convince the teacher to let me take it home so I could do it with my mother’s help.

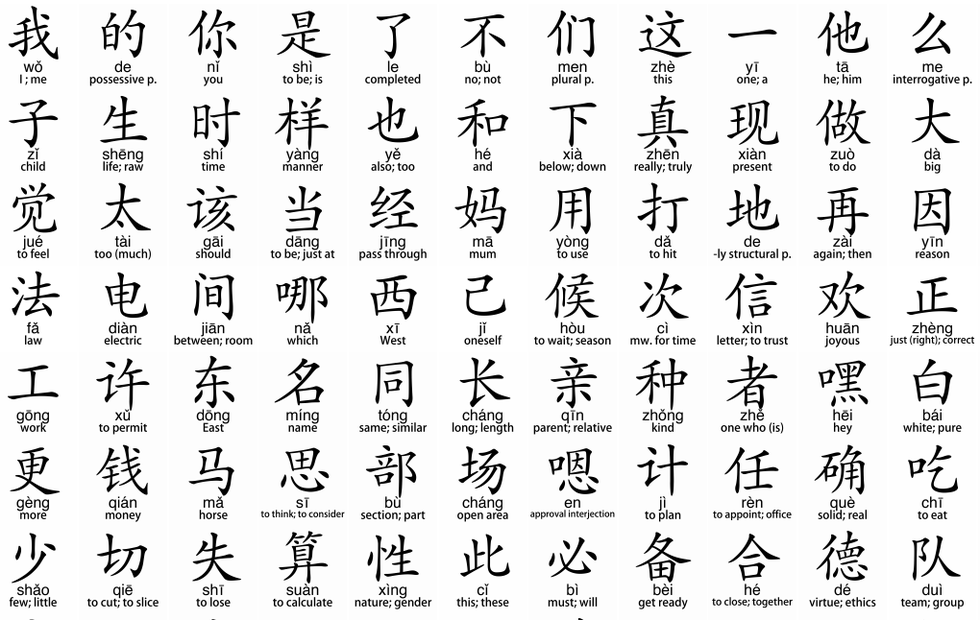

At this time, I was unaware of why I had to take this arduous language; even though my parents, cousins, grandparents and teachers spoke it, why did I have to? I lived in America, and all I needed to know was English...or so I thought. Finally, around sixth grade, my parents decided to let me quit Chinese school since I really wasn’t learning anything. As a result, my Chinese today sounds broken and foreign, and I am only able to form and read the most basic words and phrases.

Friends often ask, “You speak Chinese, right?” to which I unfailingly reply, “Yeah.” Of course, they then beg to hear a few words of the language that, to them, is a complex jargon of changs and huangs and qiaos and zhaos. Obviously, they don’t realize that the phrases I utter are layered with an English accent because of how unpracticed I am with speaking the language.

On the other hand, I reciprocate the exchange and ask them to speak their mother language. Oftentimes, I watch with envy and longing as these “demonstrations” turn into thorough conversations between those who share the tongue.

In China, not being able to speak Chinese is like (forgive the cliché) being a fish out of water. It means that I can’t talk with my cousins, my aunts and uncles and even my grandparents. It means I am silent, surrounded by laughter and dialogue, grasping for the words to express the thoughts running through my head.

Unsurprisingly, being an ABC in China invites a multitude of questions: What’s America like? Do you like China or America better? Do you like Chinese or American food better? Do you speak Chinese in America? With my limited capacity of Chinese, I often try to answer these open-ended questions to the best of my ability; sadly, my ability usually stretches only to one-word sentences.

Ultimately, my inability to speak Chinese as an ABC means being uncomfortable around those that I love. It means that I have lost a valuable skill that would’ve opened many doors in the future. And to my petulant, eight-year-old self and to others like me, I would say to learn a second language, no matter how useless it may seem at the moment. Down the road, you will be grateful that a second language allows you to be at ease with two worlds at once.