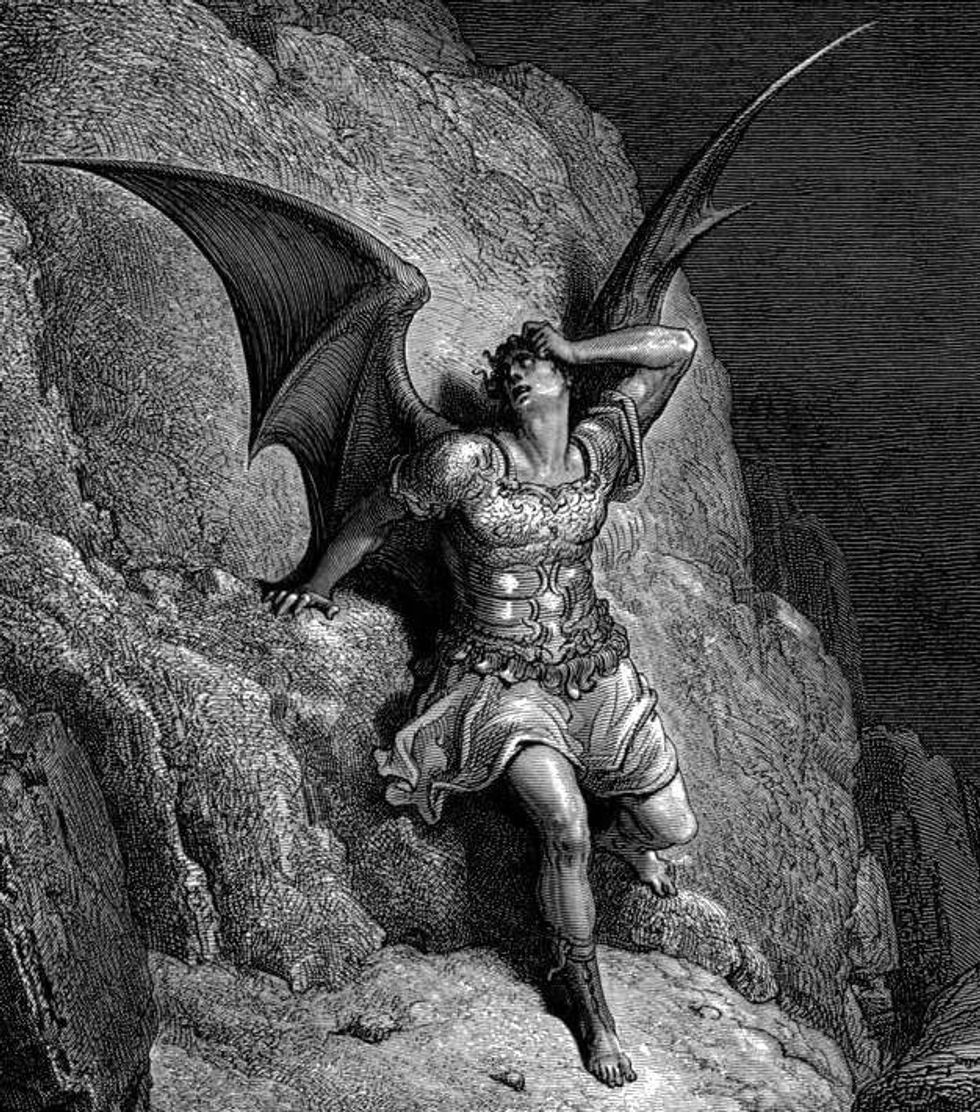

“Abashed the devil stood and felt how awful goodness is and saw Virtue in her shape how lovely: and pined his loss…” — John Milton, "Paradise Lost"

Insufferable grouch that I am, some of the well-meaning sentimental advice given to young people like myself bothers me. “Be yourself,” I am told. “You do you.” While there is a certain truth to these lifeless clichés, they do little to capture what really makes one successful or fulfilled. Frankly, “doing me” sounds like a terrible idea — “me” is lazy and selfish. “Me” writes Odyssey articles at the last possible second. I do not want to be myself. I want to be something higher than myself. I want to be good.

This year, I have been studying ancient and classical literature, grappling with the pervasive question, “What is the good life?” Sadly, I am not sure that our culture has any predominant vision of the “good life” beyond a reasonable salary, a family that gets along and plenty of leisure time. In essence, what makes you happy is the good life. How shallow, I protest. I have been deeply impacted by the notion of virtue, that there are qualities that fulfill the essential function of a human being. The virtuous person does virtuous things and in so doing leads a good life. Particularly beautiful is the Christian virtue tradition, which sees the good life as one of being drawn out of the self into love for others. Virtue brings human conduct into communication with things divine.

One of my favorite examples of virtue is the journey of Frodo and Sam in "The Lord of the Rings." Frodo chooses the dark road, the one haunted with peril and toil because it is what must be done. It certainly does not make him happy. The path is long and winding. Yet Frodo is surely one of the most “good” characters we know. He leads a good life. Sam refuses to stay behind, following his friend and master to the darkest of places for the sake of doing what is right. He perceptively notes that it is the virtuous people that we remember and honor in our tales, calling us to mimic his choice of the higher road: “Those were the stories that stayed with you, that meant something even if you were too small to understand why. But I think Mr. Frodo, I do understand, I know now folk in those stories had lots of chances of turning back, only they didn't. They kept going because they were holding on to something … That there's some good in the world, Mr. Frodo, and it's worth fighting for.”

Some object that such stories of bravery and self-sacrifice are just that, stories. But open your eyes a little, and you will see that Sam was right: there really is some good holding out, even when it seems to be drowned in all the clamor of a distracted and despairing world. On the recent anniversary of the sinking of RMS Titanic in 1914, I was reminded of the heroic souls who gave up their lives in service of others. Ask yourself which life is more good, who you would want to be: the priest who refused to board a lifeboat and went down proclaiming forgiveness to those trapped on board, or the men who had to be forced at gunpoint to give up their seats to women and children? The virtuous life requires sacrifice, and it requires courage. Truly, though, it is a good life. I leave you with some words from Sir Thomas More in the movie "A Man for All Seasons":

“If we lived in a State where virtue was profitable, common sense would make us good, and greed would make us saintly. And we’d live like animals or angels in the happy land that needs no heroes. But since in fact we see that avarice, anger, envy, pride, sloth, lust and stupidity commonly profit far beyond humility, chastity, fortitude, justice and thought… why then perhaps we must stand fast a little, even at the risk of being heroes.”