Last week I wrote about storytelling devices in video games. I decided to follow up that article with another example. Just like movies and literature, video games have merit when analyzed through an artistic lens. They have one tool that other mediums do not: the player. The best narrative games use the player and gameplay to weave a story that would be impossible to tell in any other format.

If you have any intention of playing this game, I'd advise you to do so before reading this article. "A Way Out" is a game you should go into blind.

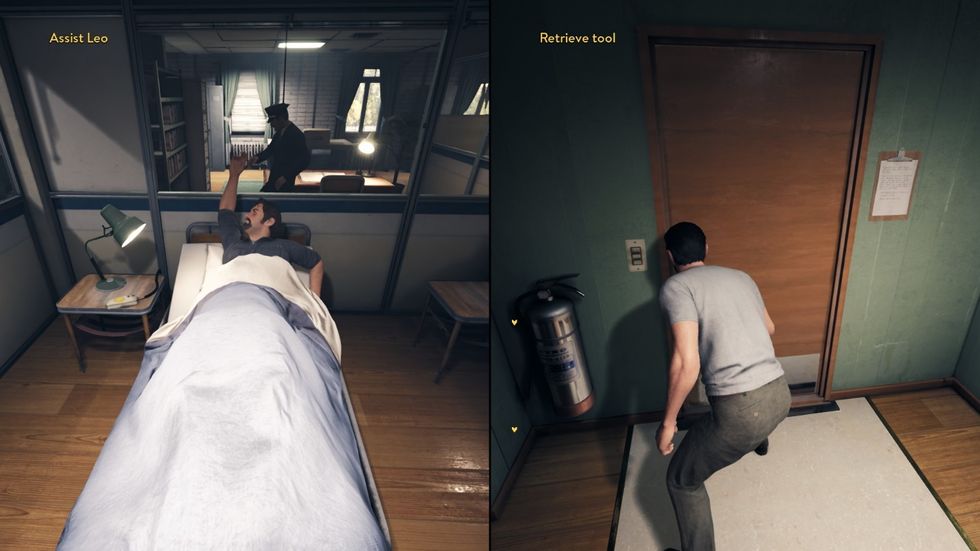

"A Way Out" is a cooperative two-player splitscreen adventure game where you and a friend play as two charming criminals (Vincent and Leo) who escape from prison and seek revenge on their shared nemesis. The game is a delightful action-movie romp, with the duo exchanging witty quips and finding themselves in tense cinematic sequences straight out of "Mission Impossible." Vincent and Leo are easily distracted—in each area you can stop to play minigames and explore the scenery. Play a banjo and piano duet in a stranger's house before stealing their car? Sure. Play Connect Four in the hospital lobby before going up to see your wife (who just gave birth)? You bet.

What makes "A Way Out" remarkable is its final sequence. The pair lands a plane, victorious, but emerge surrounded by cops. One hands Vincent a gun, who points it at Leo and mutters, "I'm sorry, Leo." A chase ensues, and the pair is separated from the police. They both acquire weapons, and two bars labeled "Vincent's health" and "Leo's health" slowly fade into the screen. My friend and I had been joking and laughing, but those health bars told us how it had to end. What followed was the longest, heaviest, most guilt-ridden shootout I'd ever played. Neither my friend nor I spoke a word, and there was no music. Just occasional bursts of gunfire while we took turns popping out from cover.

Eventually, Vincent and Leo emerge onto a rooftop and lose their weapons in a fistfight. The camera focuses on the gun laying a few meters away. The game prompts each player to mash the 'E' button like so many times before, except, instead of arm wrestling or playing an instrument, the two players are mashing to decide who lives and who dies. In my playthrough, I (Leo) reached the gun first. A crosshair appeared over Vincent's chest, and his face sunk with my heart. I've shot a lot of people in a lot of video games. It never bothered me before, and I never thought of it as murder; it was merely competition between human players in a fake world. That was the heaviest left click of my life. That's why Hazelight was made as a video game instead of a movie: instead of watching one friend kill another, they force you to do it yourself.

Vincent sits slumped on a wall and holds out the letter that Leo had told him to write to his wife. "Give my letter to Carol," he chokes out. The game prompts both players to exchange one last, the handing over of the letter, and Vincent's side of the screen slowly fades to black and disappears. Leo's view expands to the whole screen, and the presence that had been with him the entire game is gone. The music swells.

The ending of "A Way Out" hits so hard for two reasons. The first is the false sense of security the game lulls you into. The entirety of the game is an easygoing buddies-on-the-run action movie. Rarely does the game get serious, and much of our time was spent goofing around exploring each area for silly interactions. My friend and I joked about how predictable the game was. Then, when Vincent reveals he is a double agent, which blindsided us both, things get a little uncomfortable; however, we were still sure there was to be a happy ending. Then come the health bars, the music stops, and the hard truth sets in. Hazelight played us like a fiddle.

The other aspect of the ending that works so well also happens to be the exact reason why the story couldn't be told through a film: the game's use of gameplay to facilitate story. I keep mentioning the health bars because they truly are the indicator that one player has to die. Throughout the game, I bragged about how I was faster at mashing buttons than my friend—but that same button-mashing proficiency had a much more serious implication at the narrative's finale. The creators of Hazelight knew what they were doing: they were training us to kill each other.

Whereas a film might've required a series of flashbacks to remind the viewer of two characters' bond, "A Way Out" took a subtler approach by utilizing gameplay. The game is filled with shared interactions, where both players have to hold 'E' to move on. When both players push the button to save themselves and kill the other, it forces both to remember every time they did so to help one another out. Because of the way Hazelight conditions you, all it takes is one simple action to open the floodgates.

The last technique that could only be done in a video game is the splitscreen fade. For the hours it takes to complete the game, your friend's view is always there, right beside yours. When it fades out and one player is left alone, the dead character's absence is felt in a way that a movie could never have captured.

You will undoubtedly have to play the game to really feel it, but I hope that I've shown how some stories can only be fully told through a video game, one whose plot line wouldn't be as effectively conveyed in another medium. And, in the end, that's what video games are: just another way to tell a story.

man running in forestPhoto by

man running in forestPhoto by