On February 8, 2014, Emmett Rensin published a piece in the Los Angeles Review of Books titled "The End of Quitting" following the overdose and death of actor Phillip Seymour Hoffman. Six days prior to the publishing of the article, Hoffman was found dead in his New York apartment with a needle in his arm. A former heroin addict, Hoffman had been in a rehabilitation facility less than a year earlier, and died, like many former addicts, relapsing.

The article opens up with a quote from Dwight D. Eisenhower about his cigarette smoking: "I can't tell you if I'll start back up...But I'll tell you this: I sure as hell ain't quitting again."

It's a common and well-known fact, to anyone who's ever been addicted to anything, that quitting a habit is exponentially more difficult than starting it. After Hoffman passed, "embarrassment seem[ed] to be a major theme. Shame. It's a shame he had to go this way." But Rensin makes sure to follow up this point with a fundamental point: "we should remember that nobody would be more ashamed than Hoffman to see his own body, cold on a bathroom floor."

Rensin made sure, in this article, to note that this article wasn't an obituary about Hoffman's death - but rather a comment on the reaction and national conversation that happened, "about this old story we tell whenever someone dies this way." Himself a former heroin addict, all he can say is "I don't know why Phillip Seymour Hoffman was an addict. I don't know what demons might be to blame, but...I do know that the demons hardly matter."

As to why people start up opioids and heroin, Rensin says that it's not something that's very dramatic for most people, "it's just something to try...it's just the mundane." He follows up this point to comment why people keep doing it after the first time: "Usually, it's just that heroin is the best you'll ever feel, and nobody feels that way once...You use. Then it becomes part of who you are." This is a major reason why the majority of heroin addicts relapse within the first six months of treatment, and most people in Twelve Step programs drop out during the first year. "Sure, meetings help. So does therapy. But those things cannot shake the memory, not really."

For Emmett Rensin himself, he admits vulnerability in still having a moment every season where a part of him just wants to get high, despite being clean for seven years. And he can't particularly put a label or term to what that feeling is: "There aren't words for the stubborn fits of that desire. Compulsion doesn't quite capture it. Addict does, but only in an obvious, unsatisfying way."

Following Hoffman's death, many well-intentioned people, who were never addicts in their lives, expressed a sentiment that we needed to "make sense of what happened [and focus on] what we should 'learn' from this." To Rensin, these well-intentioned outcries were far more frustrating than harsh ones. There is a whole brilliantly written paragraph detailing how ill-fated suggestions warning people not to take heroin because "it's bad for you" and "people will be sad" are.

"As if the thing that stands between an addict and sobriety is the intellectual revelation of the consequences, as if heroin users are operating under the misapprehension that it's good for them...What do these friends imagine? That somebody was about to do heroin for the first time, but a quick check of their Facebook feed prevented it?"

Although he doesn't want to invalidate the feelings of these people, Rensin claims that this mindset "contribute[s] to the very culture that kills men like Phillip Seymour Hoffman,' and only adds to the shame the addicts and former addicts feel. He finds the adage that "addiction is a disease" to be insufficient - what is more accurate is that "addiction is a fundamental trait of personality...Think of it as a nasty temper: you can learn to control the rage, but sometimes you can't help seeing red."

It's important to note that people in the middle of heroin addictions rarely overdose. But those that relapse, however, do. And people who relapse, like Hoffman, know the consequences, know it's not worth it, know that you're supposed to recover one day at a time. Rensin sees this culture negatively, in that it "drives so many - even those who sought help in the past - to die in the shadows. It's just too embarrassing to admit you did it anyway. Again."

Rensin drives the point home that all of us, no matter how well-intentioned, have limits to our empathy. Empathy always has a price, one we're not always willing to pay all the way. Although we love stories of recovery and addiction, "there's a limit to the repetition we'll allow. How many do-overs is too many do-overs?...Is it five? Ten? Twelve? When does that moment come when even those who know better write off a former friend as a screw-up, consigned to a bed of their own making?"

That is one of the greatest fears of those in recovery - "a paralytic mixture of embarrassment and fear." The word "Again?" when you admit that you messed up another time feels like the end of the world. Rensin, himself, five years clean, resorted to snorting painkillers one that fall because he felt it was the "only thing preventing a full relapse." And he, just a regular person, can't imagine what it would have been like to be someone like Phillip Seymour Hoffman, "who knows full well that another stint in rehab would curry a whole world asking why he doesn't know better by now."

Who knows whether things will be different in the future, whether our cure or panacea for addiction is truly coming, whether soon "overcoming heroin will be as simple as beating back strep.". But the main point Rensin wants us to learn is that our national conversation is not helping. Most of us reading this are the loved ones, the spectators, the people whose instincts are to ask "Again?" when people relapse. If we really believed that "addiction is a disease," and wanted to live and stay true to those words, we would follow these closing remarks from Rensin:

"Until then, it's little different from cancer, and you wouldn't tell friends locked in the grip of stage-four death to remember that 'it isn't worth it.' Remission doesn't work like that."

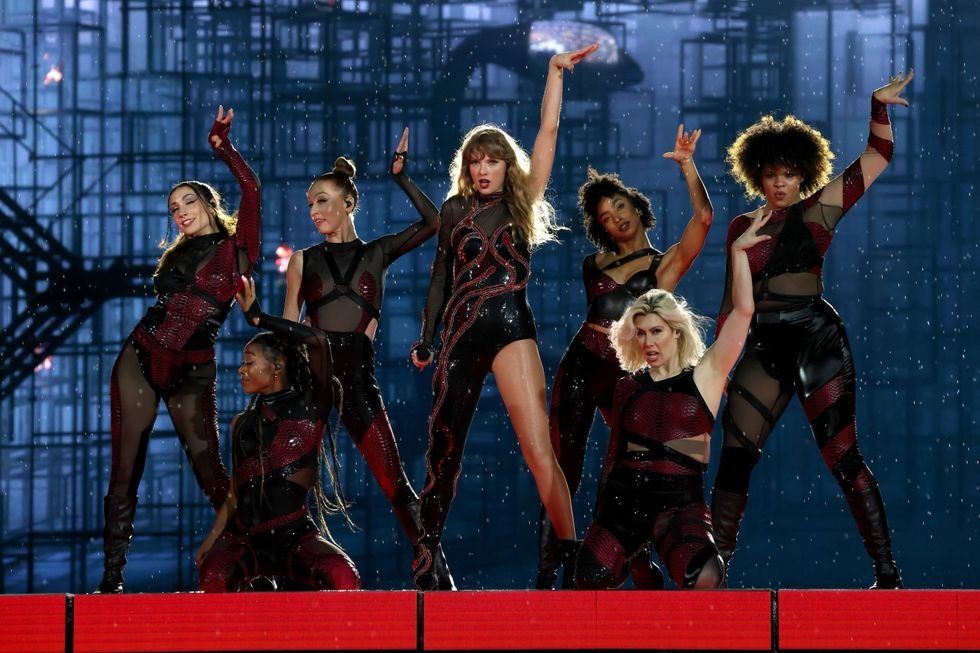

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight.

Energetic dance performance under the spotlight. Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage.

Taylor Swift in a purple coat, captivating the crowd on stage. Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots.

Taylor Swift shines on stage in a sparkling outfit and boots. Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.

Taylor Swift and Phoebe Bridgers sharing a joyful duet on stage.