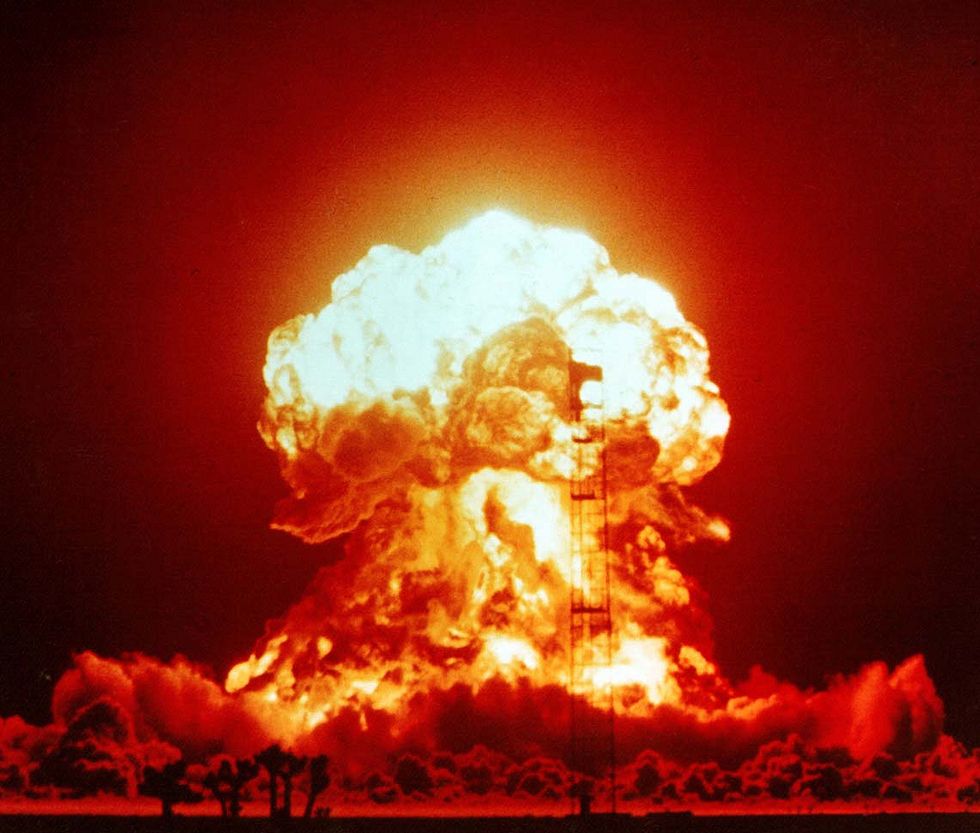

The dropping of the atomic bomb on August 6th, 1945, symbolized an end to an era; it symbolized an end to the cultural conventions and norms that existed before the war. These conventions began their breakdown at the onset of the Great Depression. The economic collapse paved the way for a more active government in private affairs. It created a trust for the government, an unfamiliar sense in Americans, a trust and reliance unprecedented in all of American history. The development of the homefront during World War II also served to change typical conventions, only in this case it served to change the idea of women in the greater society. The war effort saw an untapped market in women, a valuable source of labor who otherwise wouldn't have been able to get a substantial job elsewhere, and they used this to their advantage by promoting women to find jobs that helped our boys fighting the good fight.

Even overseas, the typical conventions were starting to shift within the military. There were over one million African American soldiers during the war, all fighting for our country, but perhaps the most well-known were Doris Miller. Doris Miller was just a staff member aboard one of the ships at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, and when he saw the Japanese planes coming over the horizon, he bravely manned the guns and tried to shoot down the Japanese. He was idolized by the masses, receiving promotional posters and advertisements praising his bravery that called on other Americans to do the same, yet he was an African American man. Before the war, these phenomena would've been unthinkable, yet before their eyes, the seeds of the new reality were coming to fruition. The bomb symbolized the encapsulation of all the forces that had weakened the conventional norms of America.

The day the United States used the atomic bomb is now celebrated as V-J day; it was a clear victory for the United States of America. People celebrated the victory in the streets, happy that the war was finally over and that life could go back to normal. Only there was no normal anymore. The bomb ushered in a new atomic age, one marked by never-ceasing fear and a sense of uncertainty, for the present, for the future, and for death, that plagued America for years to come. This was the central issue of the post-war era, then, this uncertainty that fundamentally changed all perceptions of life and death clashed with the great desire to return to the pre-war cultural conventions that had been the status quo for so long.

By examining the ways in which Americans learned to adjust to their new world it becomes clear why their culture experienced a clash of this nature that lasted for a decade. This clash contributed to a culture of chaos. Ideas of security, ideas about what the government should do, ideas about women, all clashed with existing notions as they were trying to adjust to the new reality of the atomic age, and this created an underlying sense of paranoia and fear that defined the decade after the war. No one was sure how to react to the changing national and international circumstances, whether to reinstate the old or further develop the new, and this amplified the ever-present danger created by the atomic bomb coupled with communism.

The absence of an answer created a sense of chaos, or paranoia, and that chaos eroded the existing structures of American culture. This process took place through several avenues, all of which can be broadly defined as "culture", one was the media with its immense power, another was changing political realities, and the last was shifting social expectations about women and the family life.

The primary culture makers of this time had a massive impact on the development of this culture of chaos. They encouraged reactionary responses by portraying the enemy as a grave threat, not only to international security but also to the rights and freedoms that many cherish and value in America, and this, in turn, generated more paranoia. George Orwell was one of the strongest culture makers during this time period through the publishing of Animal Farm; one of the most descriptive portrayals of totalitarian behaviors in society to date, yet he managed to do it in a relatable way that could be easily grasped by the general public. It is clear to the common reader that it is an allegory for the development of communism in the Soviet Union. In it, the animals, which represent the proletariat or the working class, overthrow the farmer, Mr. Jones, to create a society in which the animals are self-sufficient and live without hierarchy.

Quickly after the revolution, it is obvious that the pigs have established themselves as the leaders of the new group, creating a vanguard to serve the animals' needs. Eventually, the dynamics shift so radically perverting the original intent of the social experiment to support the ruling class, the pigs. The pigs represented the Communist Party in the Soviet Union, actively manipulating the minds of feeble followers to believe their twisted regime continued to fight and preserve their freedom from hierarchy, using institutions that rely on violence to support their own legitimacy. The violence and the intentional perversion of truth to substantiate the changing desires of the ruling class was perhaps the most eye-opening revelation of the behavior of totalitarian regimes. Totalitarianism necessitates these kinds of perversions in order to maintain their own power because the laws are established on the principle that they are absolute truth, but one must also accept a change of said laws or face consequences that are undeterminable.

The best example of this is near the very end after the pigs seize absolute power, they change the doctrines of the revolution to suit their quest for personal gain. Orwell writes, the ultimate doctrine of the revolution, which, in essence, is Soviet communism, was "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others." This extended metaphor that Orwell developed throughout the book is still a crucial piece of literature in understanding the nature of authoritarianism, however, its publication provided crucial insights into Soviet society that only amplified the fear of communism. A society dedicated to this idea of common ownership and "equality" tested the dearly held values of capitalism and freedom so many Americans love. A resentment towards that kind of society developed in the United States, making it easier for Americans to react with reactionary measures.

Other metaphors were developed to show the growing threat of communism, the most prominent of which is the Iron Curtain metaphor developed by Sir Winston Churchill and the idea of containment developed by George Kennan. Winston Churchill carried great esteem in American politics after the war, commanding respect for his actions in the war and as our valuable ally in fighting the enemy of authoritarianism. He delivered a speech to an American university, which was approved by President Truman, that described the looming threat of communism that was currently spreading through Soviet satellites. "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent… all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call a Soviet sphere and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in some cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow," exclaimed Churchill describing the Soviet expansion of power that threatened to destabilize and destroy the foundations of liberal democracy.

The staying power of this metaphor lies in the fact that it represented the clear dichotomy between the two opposing views; it entirely generalized an entire ideology and compared them; it never addressed the actual nature of the conflict. This made it easy to make definitive statements and draw clear goals because the details were generalized to such a large extent, which can be used to justify reactionary containment policy. A final metaphor, the one created by George Kenan, became the model of United States foreign policy for years to come. In an article published in Foreign Affairs, Kenan described the necessary policy actions that must be undertaken to ensure the demise of communism and the preservation of American geopolitical peace; he declared, "In these circumstances it is clear that the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies."

This idea that we have to contain the expansion of Soviet power was the basis for many of the proxy wars and much of the foreign policy that followed until the election of George H.W Bush, and this publication gave enough reason for Truman to act aggressively against Soviet expansion, countering Soviet moves at every possible juncture. The metaphor became the justification for almost anything, as long as it could counter Soviet expansion in the greater international community, thus creating an artificial justification for stopping anything loosely related to the communist vision.

These culture makers were the reason American culture, their society and government, developed such a strong paranoia. People were afraid of this new, unprecedented threat, and they had no conception of what to do. So they used the ideas of Kennan in the broadest sense as possible as a be-all-end-all solution that could put an end to the expansion of communism. This, however, was not the case because Kennan was only talking about the nature of the Soviets, not of the communist ideology as a whole, which gave the theory little practical application anywhere else. This idea lay the groundwork for the clash of the new and the old because it created an artificial sense of security, with security being an old value, while combining it with the ever-present danger of Russia, and the atomic bomb, looming overhead, essentially creating an uninternational framework for governing all in a simple anonymous piece.

The premise of containment was the basis of American foreign policy and domestic policy after the war; whatever could be done to prevent the spread of communism at home or abroad was just and necessary to preserve a free state. The decade after the war saw many instances of suppressing communism, or what was suspected to be communism, in any case where it was relevant. In order to stop the Soviet power, elected officials reasoned, we had to be united in the front to preserve United States freedom. At home, Truman instated loyalty oaths in 1947 in order to make sure that all members of the federal government were loyal to the United States government at all times that set the stage for the House Committee on Un-American Affairs to initiate hearings of suspected communists in Hollywood, called the Hollywood Ten.

This hearing was the prelude to countless more led by HUAC that cross-examined communists or potential communists or even people who had "controversial personalities", most of whom resided in the movie industries. However, the reality was that only a small portion of people denied jobs because of potential communist ties were in the movie industry, most were government employees who worked in the military, or as public teachers, or as civil service employees. People turned on close friends, family, and co-workers reporting them for suspicious behavior or suspected communist sympathies because they were paranoid about the fact that they may incite violence or try to spread their ideology.

The culture makers, such as Orwell, Kennan, Churchill, created the baseline for this paranoid attitude as they had painted the nature of Soviet behavior, and also of totalitarianism, in such an accurate light that people became terrified that if they were not careful, they could fall victim to these things. The Truman Doctrine shaped foreign policy, "At the present moment in world history nearly every nation must choose between alternative ways of life. . . .I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." In an effort to present it as a way to protect democracy and liberal values, he justified the use of force, however ineffective.

This method contributed to a greater culture of chaos; the ability of the president to mobilize forces to act as a counter-pressure to the Soviets in the name of containment made it unclear what our foreign policy was, always on the offensive at all times, always wary of enemy forces making an attack, bomb shelters, bomb drills, to make sure we were protected. These things became a staple in everyday American life to grant some sense of security in the face of increasing danger and paranoia that someone might attack. Truman's plan, of course, wanted to prevent this reality, but it only served to make it worse by subjecting people to greater fear that attack was possible. In the name of security, more chaos and uncertainty got created.

These ideas of security best manifested itself in the household. The general uncertainty created by the culture makers and amplified by the government started a scramble to establish security within the household. People more bought houses, went to college on the GI bill to gain access to better jobs, married sooner rather than later, and had more kids. This, perhaps, was all rooted in the deep uncertainty of the future and what could happen. They wanted households to give them a greater sense of control of their own world; women wanted to marry because they were told that they should, that it was ideal for them to reach their full potential, and men were quick to marry after the war because they wanted the sense of security given when they're able to settle down, and that was unfamiliar to them during their time overseas.

Likewise, people had more children possibly as a way to deal with future uncertainty. Women in the households also had their fair of contrasting views. "During the late 1940s and the 1950s, many women-- especially those in the middle class-- came to internalize society's ambivalence about women's nature and role in postwar America as a personal shortcoming rather than a societal contradiction," writes Stephanie Coontz about the ever conflicting nature of women in the postwar society. They were expected to be wives and mothers first, yet if they did this too much they could corrupt their children, creating "the next Hitler". Yet, they could only work if their husband said it was okay. During the war, however, they were able to work in well-paying jobs and able to work conventionally manlier jobs, and by the 1950s were immediately confined to the household.

Only then, the household was also dangerous, as if they spent too much time being a mother, they could corrupt their children. This concept of women was a contradiction if there ever was one, deeply enshrined in institutional misogyny of this area. Men were trying to cope with the new reality of the world where women had been given the right to work, had been able to experience that and proven themselves capable, yet wanting to return to a state where they were the sole source of money and power in the family. This conflict created what Coontz called a paralysis that drove women crazy.

The relation of these things is incredibly important in understanding the culture of postwar United States. The culture makers had a role in emphasizing and overplaying the new threats, spreading an amplified fear of communism and the atomic bomb that seeped into everyday life. In response to the growing fear and uncertainty created by these unprecedented and bizarre threats, the government attempted to control and contain the issue by any means necessary. This method amounted to, contrary to their intent, an even greater sense of uncertainty. The paranoia that had become commonplace seeped its way into the political sphere, tainting public institutions, that caused political vesicles to over-exert their power in order to maintain some semblance of security.

Families and citizens tried to react by creating their own sense of security; families established a patriarchial authoritarianism within the household, they built bomb shelters, had bomb drills, and constantly kept up with current events to make sure that nothing had taken a turn for the worse. This strange trends played off each other, making each other problem worse and perpetuating the continuation of such paranoia. The uncertainty that they were going to die, the uncertainty created by the ideas of communism, took hold in society and became the backbone for all cultural endeavors in the decade after the war. This was the chaos, it was the uncertainty, it was the fact of not knowing, that became the backbone. It was a series of sensitive reactions to changing circumstances.

The people, the government, and the new culture attempted to adapt to this new uncertainty by trying to superimpose the old conventions of American culture on the ever-changing circumstances that made up the decade after the war. This caused clashes in popular media, in the way our government was run, and in our everyday lives. The idea that our government was meant to preserve peace at home and abroad was taken to be true, yet we used this to justify the mass firings of thousands of people and the destruction of many people's lives, and this in effect moved us further and further from peace. Adjusting to the new atomic age was a learning process, it was a process of balancing the old with the new in order to move forward in the world, and the generation that had lived through both eras struggled to make this adjustment. The peace brought on by the bomb was a masquerade for the insurmountable contradictions by our government and the cultural tensions that paved the way for future civil and women's rights that scared the existing status quo.

It makes sense why post-war American culture seemed so volatile. It was a refractory period in the sense that it required a long settling after a large shift in cultural dynamics. The dropping of the atomic bomb spelled out a clear victory for the United States during the war, however, the repercussions of the bomb were not truly known and, in effect, it destabilized the entire culture and threw Americans into a reprehensible paranoia. This developing culture was new terrain for everyone; it scared people into reverting back into their old ways but they refused to face the reality that things were changing all around them. We can apply this same logic to other paradigm shifts in recent history, such as the onset of the internet created a culture of chaos as well, with notably less dangerous potential outcomes. When a new reality is thrust upon the world, the people in power, the majority, are unable to reconcile the new and the old, creating new tensions, and this is especially clear with the use of the atomic bomb.

This cultural phenomenon is exponentially important because we can draw parallels to today's ever-changing political atmosphere. Only instead of dropping a bomb, the cultural shift was best manifested in the election of Donald Trump. The man is a living paradigm shift; he, in his two years in office, has fundamentally changed the way we view politics. The problem, of course, is that people are not recognizing exactly what this change means for discourse. They are trying to return to a status quo, a status quo that started to disappear with the election of Barrack Obama, and they aren't trying to adjust conduct to the new realm that is American politics. If we do not change with the time, if we do not recognize the growing internal tensions within society, we may soon face an even stronger revival of the counter-culture that could throw American politics into political limbo as it did back in the early '70s. Progress is an incremental process, but if we continue to follow this path it will be akin to taking two steps back and then two steps forward every few years.

Nothing will be done. Progress starts with the people, but as is, and as it will continue to be for a while, America is apathetic and we will not care till we've already taken two steps back.