Film history is rich with a global perspective incorporating attitudes and exploring the medium. Its role expands beyond escapism to traditions and crystallizing what was wanted. Even productions from decades ago remain timeless, applicable to post-modern ideas and lifestyles. Directors sought to make period pieces that captured their country's image while others used every shot for the depiction of interpersonal communication.

Questions in relation to its limitless capabilities have been asked and answered by the finest crews, from what is cinema to what can cinema do? The role of film has shifted substantially, shaking its image as a literary adaptation to an outlet for visual pleasure, and assuming a social aspect with documentary works. From crass extermination, counterculture, and informational dissemination in censored states, these are eight major film movements in Europe you should know.

1. German Expressionism

A period of writing, art, and film embedded lingering remnants of the anger and fear locals felt after defeat in World War I. Films became an importer fixture to everyday life in the 1910s because of foreign movie bans. It made a space for Germans to create for themselves and what they held dear. Capturing intimate, inner feelings filled this 1920s movement.

Movies of this style tend to counter typical Western movies and abandon reality. This was in part because directors felt that film was a form of art only to the extent that it strays from real life, taking on a new form of its own. Plots favored the hyperreal or fantasy for escapism because reality was too limiting and bleak. Visible on screen is the subjective mood of isolation Germans felt in a dark time.

The expressive imagery was seen in endless roads, dystopia worlds, absurdity, and limitless possibilities in the screenplay. German Expressionism would spill over as exports to other European cinema powerhouses.

2. Soviet Montage

Film theorists shined a light on film's need for formalism, believing in the importance of contributing elements such as lighting and sound. This movement changed the way editing would be executed in cinema, seeing every cut as a moment to innovate and move the viewer.

Using overtonal montage editing, directors took tender care to observing metrics, rhythm, and tones as factors to bridge independent shots together. Rather than show an action in its duration or feel the need to have a character explain what is unfolding, editing utilizes our ability to rationalize and connects ideas. Overtonal montages cannot be complete without evoking ethos or pathos in its audience.

Revolutionary at its time of conception in 1920s Communism, these films fixated on individuals rather than collective experiences shared by groups of people. It epitomizes the medium's ability to stand in protest with its existence. Documentarians regularly reflect on this style.

3. Italian Neorealism

This movement rejected cookie-cutter endings and shined a light on the everyday realities faced in the world. Like many others, this shift was born from the harrowing effects of World War II where people reflected on life and had angst about the future. Standards included long shots with takes that seem endless, as well as small details to capture moments in live time, such as people cleaning piece by piece.

Working class, anti-hero, and regular people were at the forefront of narratives. It gave viewers someone to relate to and sympathize with. Fittingly, stars were rarely cast. Ironically, Italian neorealist films would become predictable too since viewers began to expect that desires would not be fulfilled and the endings would not be celebratory.

4. The Polish Film School

Spanning from 1955 to 1961, this was a period for Polish filmmakers to dedicate time to reflect on how World War II affected the country during and afterward, looking at the harrowing discoveries of the Holocaust and soldiers. The school itself was made in 1948 to offer citizens the opportunity to pursue film academically.

This was not a renewed interest in war themes, but rather when state censorship eased on historical depictions. Filmmakers had eagerly waited for this opportunity and executed it similar to Italian neorealists, feeling the mood could only be captured with bleakness. Reflections were also on what it meant to be Polish.

Highlighted here is a motif of how films can be restrained to governing politics and ulterior motives, sanitizing a national cinema. Also, it shows just how powerful movies were to informational dissertation and historical importance.

5. Art Cinema

Art cinema rose to popularity in the 1960s. It was a rejection of contrite formulas and shallow narratives in American Classic Hollywood films. This period created works that value aesthetics and reasoning for transformative viewings. Also referred to as art house, these films are not made for mass appeal or escapism. Instead, they seek to explore lesser-known topics and require close readings.

Associated with Second Cinema are the Auteur Theory and national cinema. They are popular on the indie circuit even though box office performance is rarely a factor in conception and release. Formed in reaction to First Cinema, art house films rebuke its passive consumption. First Cinema heavily seeks to replicate a reality many are familiar with and shows humanity at surface level. Studio productions wrote films to generate money in the grand scheme of profit motives.

Filmmakers felt there needed to be aesthetics rather than happy endings and constant action. Purposely, art house films embody subtleness and symbolism. Shots regularly cut to static walls or conversations take up a considerable amount of screen time, engaging a viewer in a different manner.

Similar to Italian neorealism, major stars are rarely cast. This is in part because of the low budget with which creators are unable to afford high wages, but also not to make an actor bigger than the film or cause a viewer to associate them with another role. Absent is politics, which would evoke the birth of Third Cinema by artists who felt colonialism needed to be depicted too.

6. French New Wave

Leading up to this movement, famed French critics such as Truffaut were bemused and disappointed with the industry. He saw his national cinema as an over-glorified literary adaptation with no input or realization of the film medium itself. Rather than faithfully translate literature, cinema should create its own plots or at least tell the story using film's different execution.

Truffaut believed cinema should be more than what it had initially aspired to be and greater attention had to be given in image-making. His critical essay, La qualité française or "The French Quality," released in renowned French film magazine, Cahiers du Cinéma, shook the world and invoked a moment of reflection.

The French New Wave movement began in response to him in the 1960s. Produced in the spirit of Auteur Theory, in which the director is a major figure to filmmaking and should place their personal style into the film, cinema was playful and birthed new techniques.

Jump cuts made their way to existence, manipulating time and disrupting traditional invisible editing. Running complimentary is the employment of handheld cameras. Shaky, you can film movement in the frame and it diligently keeps with the on-screen suspense.

Films no longer attempted to hide their design, but rather call attention to their elements. Actors regularly broke the fourth wall, looking into the camera to acknowledge the viewer. French New Wave owes a lot to Classical Hollywood cinema, particularly film noir, and is a fitting tribute.

7. Italian Giallo Horror

It owes its name to the cheap paperback comic books made during the Benito Mussolini years when bans were levied of American and British exports. The yellow background cover was a distinct feature of the popular mystery and crime literature. The 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s would birth a slasher-style film movement inspired by them.

Distinct traits include gore, female victims, and madmen assailants with black gloves unleashing terror with little supernatural element present. The killers would have great attention to detail, rather than appearing on screen at brief moments of terror. Some films would show their first-person perspective or heavily include them into the plot. However, Giallo did not always offer motives or solid explanations, with psychological factors being one aspect.

Structurally, bright colors, lyrical music, stylized movie titles with numbers and animal names are common elements. Perfect for any Halloween viewing, Italian Giallo films were a point of reference to horror enthusiasts that cared just as much for bloodshed as aesthetics, but more so than plot.

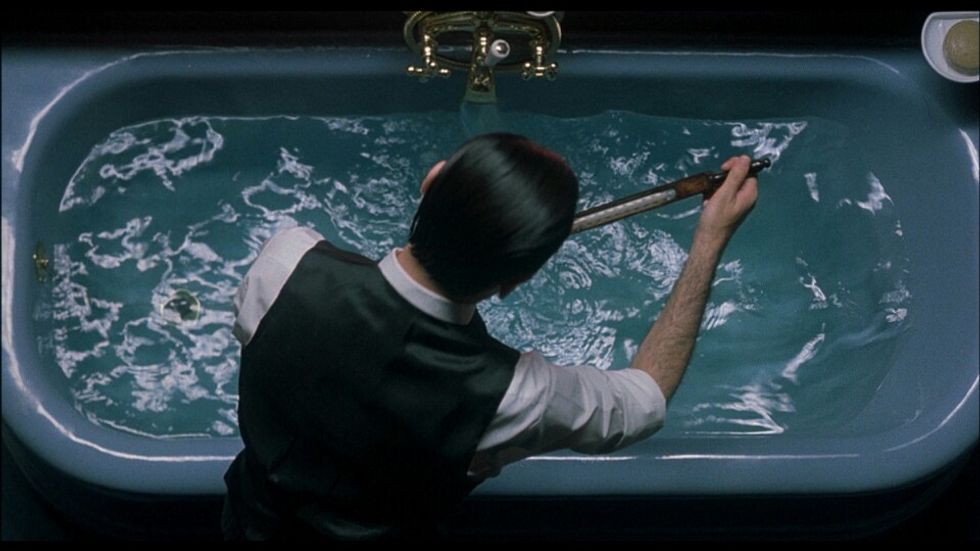

8. Cinéma du look

This was a rather brief movement in French cinema, from about 1980 to 1991. The visual style was by far its point of interest, creating glossy and transformative experiences on screen in light of emerging technology. It prioritized aesthetic over plot, largely ignoring developing characters by devoting time to their mindsets. Outlandish and familiar pop culture iconography mixed with the aristocratic high culture.

Cinéma du look did not escape backlash, with some critics accusing its directors of using film as a mindless rehashed marketing tool rather than with diligent purpose. Jean-Jacques Beineix's 1981 French thriller film "Diva," which kicked the movement off, has been favorably hailed, however. Deemed a relic for postmodernism, "Diva" remains a major fixture to Cinéma du look.