June 23, 2016 was a day full of eye-catching headlines. The "sit-in" in the House of Representatives by several House democrats ended, the British referendum on their future in the European Union was undertaken and the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a 4-4 ruling on President Obama’s controversial immigration law, allowing the decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals to stand.

Lost in the news, however, was any meaningful coverage on the bilateral ceasefire and disarmament deal signed by the Government of Colombia and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), effectively ending the longest lasting guerrilla conflict in South America. The war has lasted 52 years, killed over 220,000 people, and internally displaced another 6.8 million (the second largest IDP population in the world behind Syria). Over 80 percent of the Colombian population have lived their entire lives within the conflict, and this agreement is the first real step on a long road towards peace for the country.

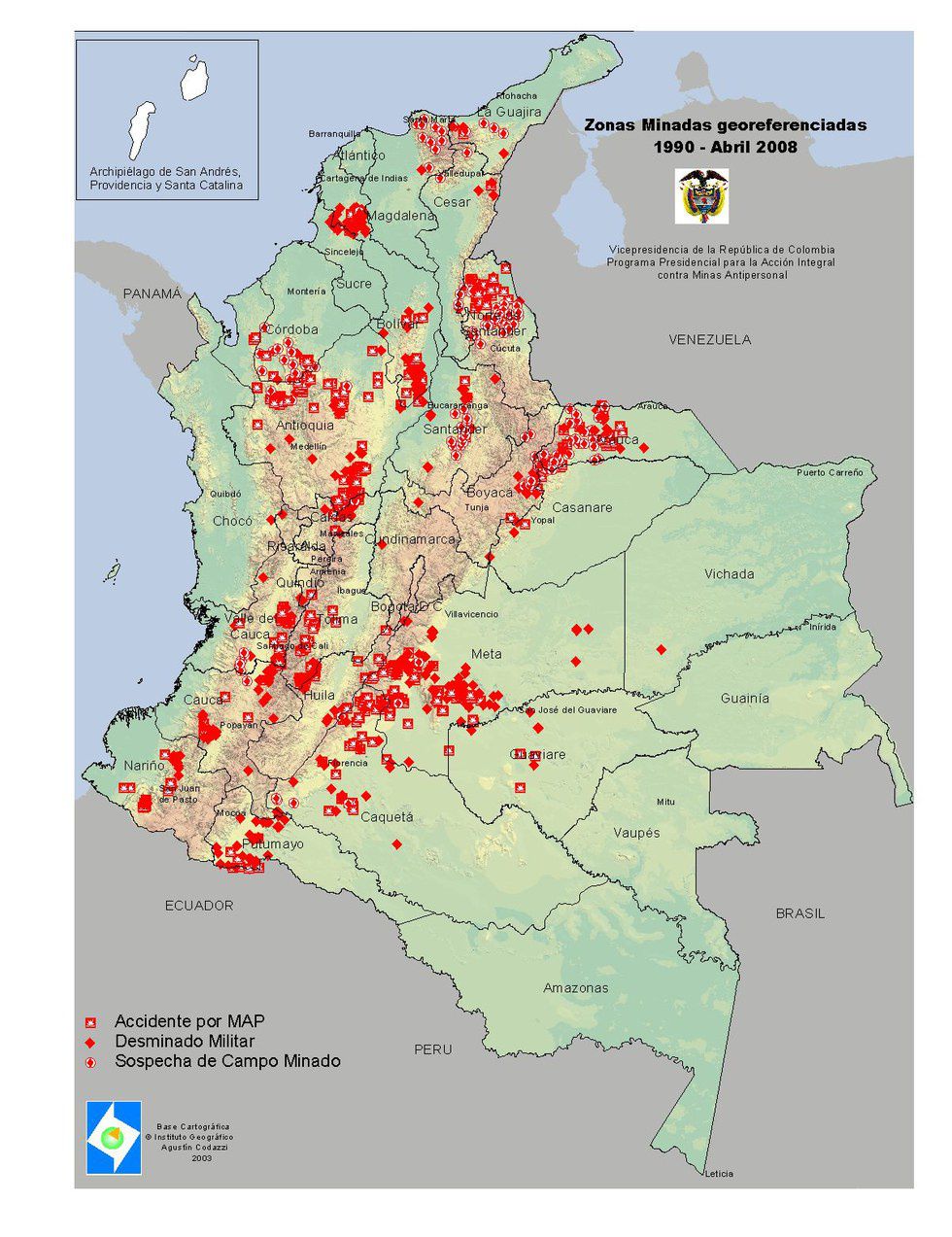

Figure 1. Map of FARC-controlled territory in Colombia

First of all, it’s crucial to understand the beginnings of the FARC. The group can draw their roots back to the period known as La Violencia, which lasted from 1948 to 1958. When left-leaning presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was assassinated in the capital city of Bogotá, a spontaneous riot broke out that killed nearly 5,000 people within 10 hours. In the following ten years, peasants aligned themselves with either the Liberal or Conservative party in a civil war that ultimately killed 200,000 people, with many of them tortured or killed in brutally cruel ways. When the conflict ended, power was consolidated among the Conservative and Liberal elite and the military was greatly strengthened to prevent any future peasant violence.

Rural farmers had their land forcibly taken from them and many had to migrate to urban cities to work, essentially as indentured servants. As Marxist-influenced sentiments began to take hold in rural towns, the government acted swiftly and violently to eliminate any anti-government beliefs. After 16,000 Colombian soldiers attacked a village of 1,000 people, of whom only around 50 were armed, a pro-Marxist leader, Manuel Marulanda Vélez, fled to the jungle and founded the FARC to protect the interests of rural farmers and oppose the growing power of the Colombian elite.

Figure 2. A train car burns in front of the Capitol building during La Violencia

Now, what may have grown out of honorable intentions quickly devolved into a corrupt and violent entity in the Colombian countryside. FARC leaders have been complicit in human rights violation and systematic sexual assault by their soldiers within the territory they control. They have routinely used kidnapping of political figures, extortion of rural farmers, armed robbery, and carjacking as a means of financing their war, and have become nearly inseparable from the illicit cocaine trade that Colombia is so well known for. The United States Justice Department, in a 2006 indictment of several members of the FARC, presented evidence that the organization is responsible for 50 percent of the world cocaine production and 60 percent of the cocaine that enters the United States.

The FARC have also destroyed the livelihoods of the citizens on the borders of its territory by mining the areas, preventing rural agriculture, and consistently kidnapping children to serve as child soldiers, much like the infamous warlord Joseph Kony did in Uganda. The FARC also overran areas set aside by the government as national parks, and instituted poorly planned and improperly executed deforestation and illegal mining operations, the run-off of which has contributed to the unbelievably high levels of mercury in Colombian drinking water. Quite simply, the FARC went from a group designed to protect the interests of rural farmers to a crime syndicate that uses fear and violence to enforce rule over the Colombian population both within and outside of the territory they control.

However, one can not claim that the Colombian military and paramilitary forces are faultless. In the Uribe Agreements of 1984, the FARC negotiated an end to the conflict in exchange for guaranteed political participation and agrarian reform. The FARC subsequently formed the leftist party "Patriotic Union" (UP). After winning 4.54 percent of the national vote, nine seats in the House of Representatives, and five seats in the Senate in the 1986 national elections, 21 national and local lawmakers, 11 elected mayors, and nearly 5,000 UP supporters were murdered by forces sympathetic to (or under the direct command of) the ruling Conservative and Liberal parties. In a more contemporary example, indigenous communities in the department of Nariño, which forms the South-West corner of Colombia, have told of truly brutal treatment of FARC child soldiers by Colombian military.

Reportedly, the military will bury youths up to their necks in the jungle and leave them there for two days. After coming close to succumbing to exposure and dehydration, the military will dig the adolescents out of the ground and take them prisoner. This human rights violation is, apparently, the military's best idea on how to discourage discontented youth from joining the FARC. Rather than addressing the underlying issues driving FARC membership, military leaders have ruled through cruelty and fear, blurring the line between the nationally sanctioned military and the very soldiers they are fighting against.

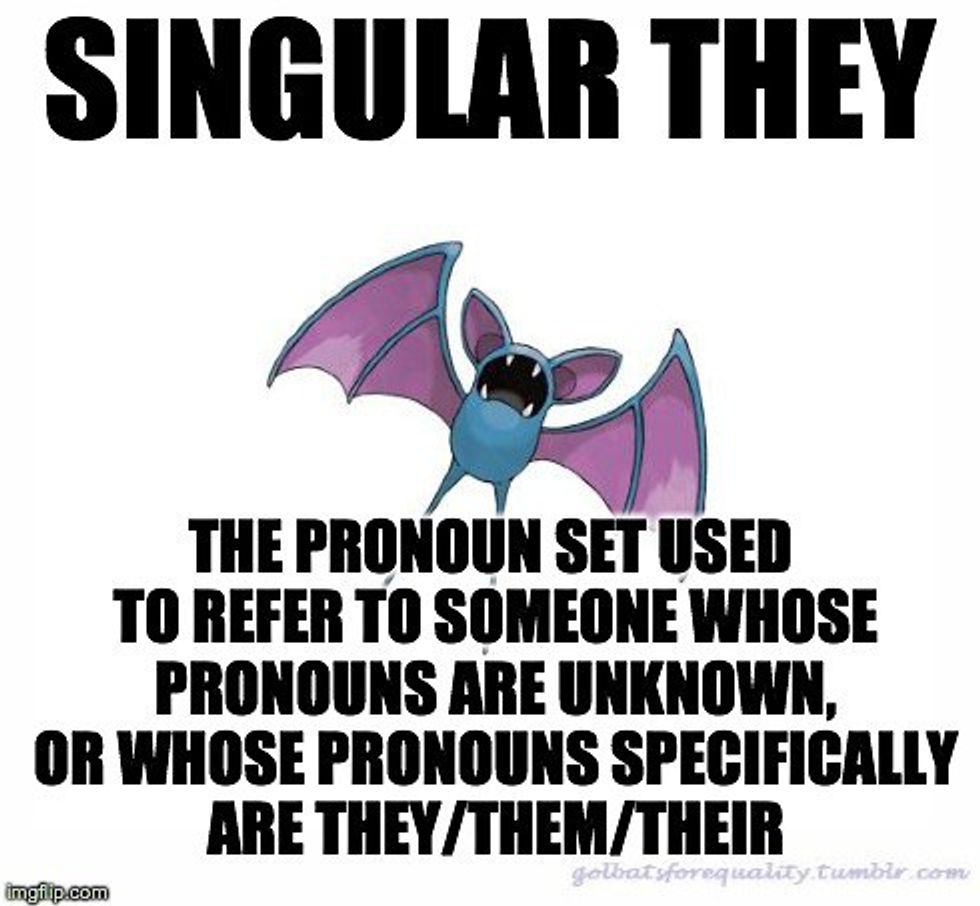

But, on the morning of June 23rd, the first concrete step towards the dissolution of the FARC began. Within the terms of the peace accords signed in Havana, Cuba are plans to turn over all guerrilla weapons to the United Nations by January 23, create 23 “Temporary Hamlet Zones” in conjunction with the UN monitoring mission to serve as areas of demobilization and repatriation, suspend all warrants for properly demobilizing FARC soldiers, and, with the assistance of the FARC, remove all land mines and unexploded ordinances in the rural countryside (See Figure 3 below).

Now, this all sounds as if it is a dream come true for the Colombian people. The war will end, citizens in large cities will no longer have to fear encroachment from FARC forces, and aid organizations can reach populations that have been isolated for decades.

Figure 3. Map depicting areas of mine accidents, military demining projects, and areas of suspected mines and unexploded ordinances (2008)

Contrary to what would be expected, however, is the cloud of apathy resting over the citizenry of the capital city of Bogotá. I was in the city the day the agreement was signed, and can attest to the fact that there were no parades, nobody cheering in the streets, and little celebration within office buildings. Aside from some mildly excited conversations at the water coolers in the morning and a short-lived blitz of local media coverage, it was a deceptively normal day. Quite simply, the people here are fearful that this peace is not going to last and are very hesitant to get their hopes up. In the past, as mentioned above, the 1985 peace talks ended with a political massacre.

The peace talks that began in 1998 ended in 2002 after the FARC hijacked an aircraft and kidnapped several political figures. Since this round of peace talks began in 2012, FARC soldiers have killed 19 soldiers and kidnapped a Colombian general. And, since the peace treaty was signed, the UNDSS, the internal security branch of the United Nations, has already documented six instances of the treaty being breached since the adoption of the deal. The populace, rightly so, distrusts the FARC and are reluctant to believe they will honor their end of the treaty.

And, even if the FARC leadership follows the agreement to a tee, there are legitimate reasons to fear that this simply will not bring peace. The government’s plan for repatriation is going to isolate the demobilized soldiers in rural areas, where they are going to lack education and vocational training beyond what the FARC can provide. It’s reasonable to assume that the same economic and political discontent that originally founded the FARC could recur within the demobilizing soldiers, and the people who were raised to lash out in violence against any government encroachment may look for alternative outlets. There are still multiple rebel groups within Colombia, albeit with much smaller influence than the FARC, and they likely will heartily accept any discontented soldiers who refuse to give up the fight.

Entrepreneurial FARC soldiers looking to start their new lives off with a bit of capital will also find many willing buyers for their arms, essentially sidestepping the United Nations decree to turn in all guerrilla weapons. Furthermore, all of the arms that are turned in will be kept in the Temporary Hamlet Zones under the supervision of the UN until the end of the six months allotted in the peace treaty. No government soldiers are allowed within a kilometer of the Zones and the FARC soldiers are not permitted to remain armed. With one offensive from another guerrilla group, such as the traditionally violent ELN, we could see, with little resistance, hundreds of guns, grenades, and land mines fall into the hands of another group, essentially rebranding the Zones as a conduit for the redistribution of violence. Additionally, the government is already preparing for guerrilla groups to fight to fill the power vacuum left by the absence of the FARC.

The mechanisms to run the drug trade, operate illegal mines, and exert control over rural farmers will not immediately be dismembered by the treaty, encouraging opportunistic expansion of other criminal and paramilitary groups. Lastly, there are citizens who have legitimate complaints over the suspension of warrants for FARC soldiers. Many of these militants have committed murder, rape, and extortion in and around the small villages where they will now be held, without any legal consequences. How can we expect a family whose daughter was raped by a FARC soldier to carry on with their lives while allowing the same soldier to integrate into their village? That question is not hyperbole; it is testimony of a mother from a small village in Southern Colombia. It is highly possible that citizens of rural towns will block the reintegration of soldiers, again promoting them to seek out other violent groups (See Figure 4).

Figure 4. Members of the Colombian opposition party protest the suspension of warrants for FARC militants

There is a lot that can go wrong, but there is an equal or larger amount that can go right. By strategically implementing the right policies and activities, the United Nations can prevent arms from falling to other groups and accelerate the reintegration of soldiers. By refusing to waive the warrants of the FARC soldiers directly accused of human rights violations, the Colombian government has shown solidarity with some of the victims in the rural countryside. And by sharing the stories of already demobilized FARC, those that fled the organization prior to the peace deal, the media can help normalize these people in society.

While these peace accords are clearly far from perfect, they are the official end to a conflict that has lasted 50 years, caused the deaths of 220,000 people, and forced 30 times that amount to flee their homes, jobs, and livelihoods and live in refugee camps with no hope of improving their condition.

While it is conceivable that this peace will not last and other groups will lay their claim as the most dominant force in Colombia, this deal should be celebrated and acknowledged around the world. People are even discussing the possibility that the Colombian president, Juan Miguel Santos, receives the Nobel Peace Prize for this deal. A country of 48 million people has finally found peace, and now they are beginning the long road of ensuring it is a lasting one.

Figure 5. Colombian President Juan Miguel Santos (Left) and FARC Commander Timoleón Jiménez (Timochenko) celebrate the signing of the peace deal