Recently, there has been much squabbling over the much-misunderstood term “feminism.” Now, before you click away from this article, I will not be gracing you with my opinions of women’s rights. Are you here to stay? Good, because the topic of role models is a universal one. I believe there to be a severe under-representation of women in today’s mainstream education. Learning about the great feats of men is wonderful—a man can absolutely be a woman’s role model—but there is something to be said of looking up to someone of your own gender or race. A recent study in Forbes magazine stated that in the West Bengal region of India, where quotas for female politicians are met, the gender gap in teen education disappeared. Parents are becoming equally as ambitious with their daughters’ education as their sons’. Seeing women in charge—running things like political groups, leading teams of engineers, spearheading new developments in equality, science, and literature—encourages young ladies in school to pursue their dreams; it gives them the courage to dive head first into daunting new things, because they know that women before them have done the same and succeeded. I believe one of the first steps to be taken in the pursuit of equality, dare I say feminism, is to give our fellow women the chance to learn about those who came before them, so that they may find themselves inspired. In the pursuit of that goal, I have compiled a list of 5 amazing women in history who are often left out of history books. I hope you find yourself inspired by them, and get excited about the possibilities in front of you.

1. Ada Lovelace (1815-1852)

"That brain of mine is something more than merely mortal; as time will show."

Nicknamed the “Enchantress of Numbers,” Ada Lovelace was the only legitimate child of poet Lord Byron. Unusually, her mother brought in tutors to teach her science and math (not very common with girl’s education during this time period). She later studied advanced mathematics at the University of London, and received instruction from Mary Somerville, one of the first women to be admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society. She worked closely during this time with Charles Babbage (the father of the computer), and published a commentary on an article describing Babbage’s analytical engine, an early calculator, essentially. Not only did she understand and describe the inner workings of this machine in detail (her commentary was three times as long as the original article), she theorized method for the machine to follow a series of repeat commands, known as looping in computer programming today. Ada Lovelace is thought of as the first computer programmer, though her works were not discovered until 1950, and she never attracted much attention on the subject while she was alive.

What we can learn from Ada Lovelace: Although we don’t always see the fruits of our labor, doesn’t mean that it won’t impact the world in some way; don’t work for accolades, work to progress.

2. Nellie Bly (1864-1922)

"I said I could and I would. And I did."

Born Elizabeth Cochran and writing under pen name Nellie Bly, she got her start in journalism responding to a misogynistic editorial entitled “What Girls are Good For”; editor was so impressed with Bly’s tenacity he gave her a full time job at the paper. Later in New York, tired of writing solely for the women’s page, she landed a job investigating the Women’s Lunatic Asylum in Blackwell Island. She pretended to be insane, even tricked doctors ("Positively demented," said one, "I consider it a hopeless case. She needs to be put where someone will take care of her"), all in order to be committed to the asylum, to get an inside look at the secretive practices of the place. “Ten Days in a Mad House” caused a huge sensation and even led to a grand jury to condemn the asylum for cruel, draconian practices (think rats, rotting food, and ice-cold "baths”), as well as a one million dollar raise in the budget of the department of charities and corrections, to fix these problems in the asylum system. After her asylum expose, she beat Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days by 8 days, completing the trip with only one dress, several changes of underwear, a study overcoat, and one bag with her toiletries. In an industry and world that was tough on women, Nellie Bly did not give up, lose hope, or let outer circumstances determine her tenacity.

What we can learn from Nellie Bly: Bravery, determination, and ambition are not only traits of men, they can take us just as far as Nellie Bly, if only we use them.

3. Mary Jane Bethune (1875-1955)

"The whole world opened to me when I learned to read."

Born into slavery, Mary showed an interest in education from an extremely early age. She came to believe that the only difference between white Americans and African Americans was the ability to read and write; she became wildly inspired to learn. She was the only one of her family to attend school and after walking five miles back home each day from Trinity Mission School, would teach them what she had learned. Mary went on to attend, with scholarship, Scotia Seminary and Dwight L. Moody’s Institute for Home and Foreign Missions, with the idea to become a missionary in Africa. Denied this goal, she decided to teach in America. In 1904, she started a small private school for African American girls in Florida, emphasizing a curriculum of self-sufficiency as women; this later developed into Bethune-Cookman University. Mary was appointed as an adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt as part of the Black Cabinet, and came to be known as the “First Lady of the Struggle” because of her commitment to bettering the lives of African Americans. Upon her death, columnist Louis E. Martin said of her, “She gave out faith and hope as if they were pills and she some sort of doctor.”What we can learn from Mary Jane Bethune: Education is amongst one of the most important things that we have, we mustn’t squander this opportunity; we can learn a little from everything, and that can take us places, no matter where we come from.

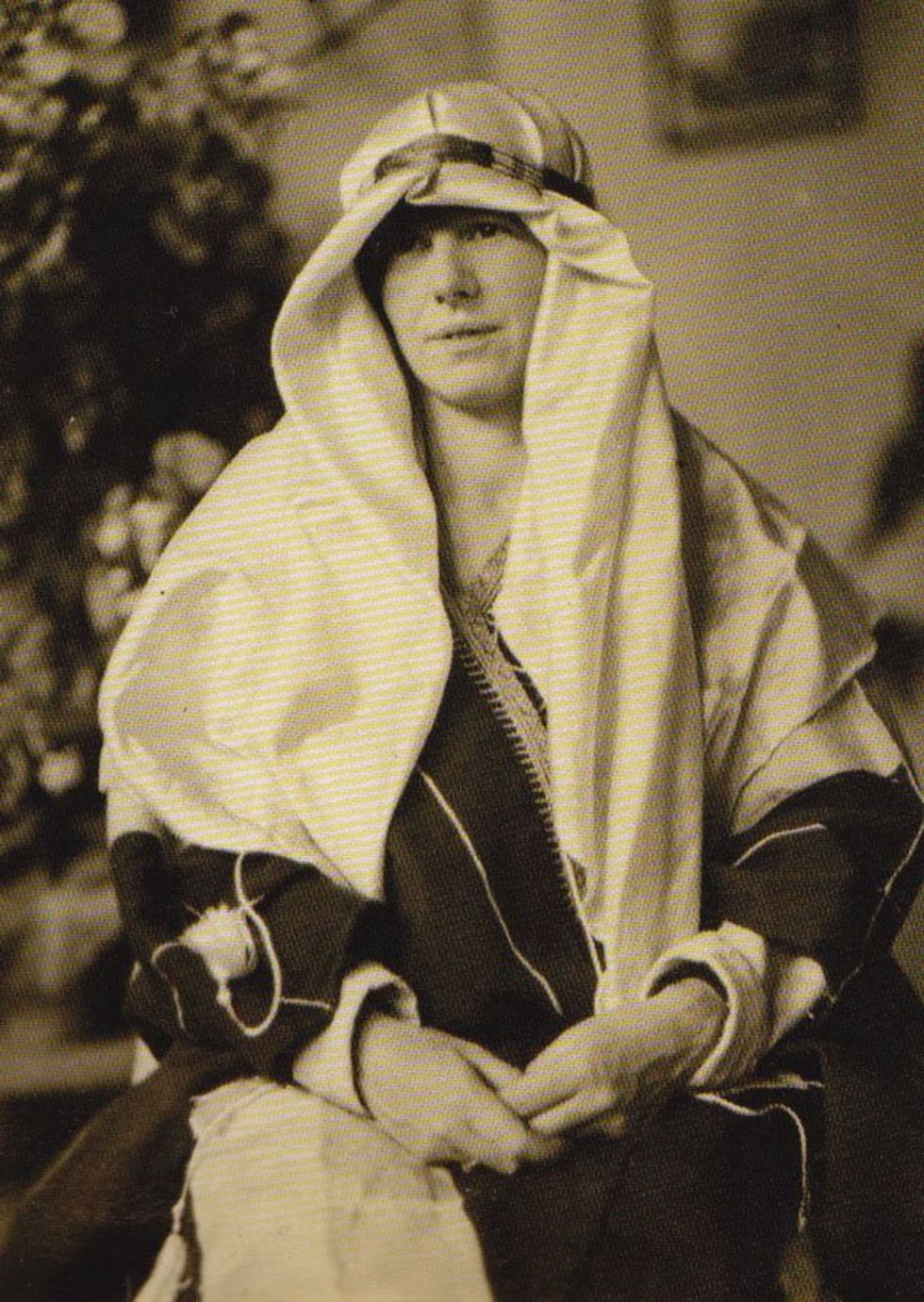

4. Freya Stark (1893-1993)

"To awaken quite alone in a strange town is one of the most pleasant sensations in the world. You are surrounded by adventure."

Freya Stark was born in Italy and raised by rather liberal-minded parents, her mother and grandmother being the role models of her life. She was taught mountaineering and horseback riding along with traditional education at the time, and learned several languages at a young age. Beginning with Latin, her language lexicon eventually expanded to include French, Arabic, and Farsi. Freya received One Thousand and One Nights for her ninth birthday, which began her fascination with the Middle East. After a stint as a nurse in World War I, she descended upon Persia. By 1931, she had taken 3 trips into Western Iran and located the Valley of the legendary Assassins, founded around 1080. As one of the first non-Arabians to trek through the Arabian Deserts, and a woman at that, this was an incredible feat; there were many times she could have been outright killed. These trips began a whole life of travelling this region and further. At 76, she made trips back to Afghanistan and Iraq; at 86, she travelled to Annapurna and the Himalayas. Living to be over 100, Freya Stark never lost her wonder for the world. Her travel essays have been published into several wonderful books and journals.

What we can learn from Freya Stark: Chasing our passions, even ones we acquired at a young age, is so important and can often lead us on exciting adventures.

5. Noor Inayat Khan (1914-1944)

"Liberté!"

Noor Inayat Khan was of royal Indian descent, born in St.Petersburg in 1914. Her family eventually migrated to England during the course of WWI, and by the time WWII rolled around, she and her brother Vilayat, decided to get involved in the fight against he Nazis. In 1940, she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, and later was selected as a Special Operations Executive agent in France; though her training was incomplete, her fluency in French and competency regarding wireless transmitter systems made her an excellent candidate. She travelled to Paris with three other women and immediately began undercover work; it eventually became extremely dangerous and Inayat was offered a one-way plane ticket back to London, which she refused, being the last wireless operator in Paris. She became Paris’ most wanted British agent, highly sought after by the German SS; she continued to transmit information and helped keep together the allied Prosper circuit network. Eventually Inayat was betrayed to the Germans and underwent extreme interrogation and torture, during which she did not give away a single piece of information, as attested to by her Gestapo interrogators. In 1944, Inayat and three other agents were executed by the SS; it is recorded that her last word was “Liberté!”

What we can learn from Noor Inayat Khan: Inayat Khan never let fear keep her back from doing what was right in the fight for freedom. In whatever we are called to, we cannot let the grip of fear keep us from accomplishing our goals.