In our attempts to see justice done and to discourage bad behavior, we often turn to punishments to teach those danged criminals a lesson. Frequently, however, those punishments are unhelpful and can even be completely counterproductive. Here are three myths about the way that we punish criminals in the United States:

1. "Torture can get useful information."

Let's assume for the sake of argument that torture is morally acceptable and assess purely on the basis of whether or not it works. Given that the goal of torture is to get information, it is basically useless. Actually, it is worse than useless. Researchers have consistently found that it provides false and misleading information.

The United States Army Field Manual warns that information gathered by torture can be faulty. That's because, during torture, truth becomes irrelevant. And when the interrogators don't know if the information is true, the torture may continue even if the detainee tells the truth. At that point, the captive will fabricate information with the goal of telling the interrogator what he wants to hear. "It is enormously well documented (including by the Senate study of the CIA program) that torture generated enormous amounts of false statements," said Lisa Hajjar, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Many interrogators have thought they can tell when a tortured subject is lying, but their guesses were no better than flipping a coin. Members of the Bush administration claimed that torture helped the Bush administration during the Iraq War, but it didn't. Most cases of supposedly successful torture they named have since been debunked. It is unfortunate that they decided to legitimize torture, since even before the 9/11 terror attacks, "the CIA itself determined from its own experience with coercive interrogations, that such techniques "do not produce intelligence," "will probably result in false answers," and had historically proven to be ineffective. Yet these conclusions were ignored."

Even without the substantial ethical objections, torture is not worth it – especially considering how it damages our reputation abroad.

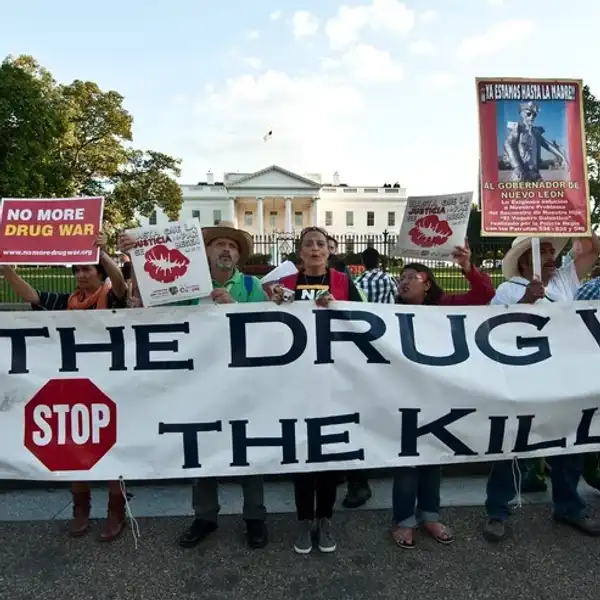

2. "The War on Drugs is working."

The War on Drugs is failing partially for the same reason that Prohibition did: the laws of supply and demand. Trying to remove all drugs using government force lowers the supply of drugs, which raises their price, compelling more drug providers to enter the market to make a profit. The result is a frustrated government spending $500 per second (over $1 trillion in total since Nixon) locking people up at an unprecedented exponential rate.

Beyond that, our approach to the drug addiction has been fundamentally flawed. We have often assumed that taking drugs – especially "hard-core" drugs like heroin – for a long period of time must lead to addiction. But hospital patients who are hooked up to morphine rarely, if ever, end up addicted, despite the fact that they receive a much purer and stronger form of heroin.

One reason that researchers found why those patients do not become heroin addicts is a stable social environment. In many drug experiments, a rat was put into a tank with two water feeders, one normal and one laced with heroin. Unsurprisingly, the rat became addicted and only drank from the heroin water. Experiments which stopped there were used to justify the War on Drugs. However, when Bruce K. Alexander ran the experiment again with more mice in a larger tank including a "playground," the mice drank almost exclusively from the non-heroin water. Mice became addicted only if they were socially isolated and deprived of other sources of happiness.

So criminalizing heroin and other drugs has not only backfired economically like Prohibition did, but it has also backfired by forcing drug users into the conditions where they are most vulnerable to addiction: homelessness, social isolation and deprivation of other sources of happiness.

To be fair, the validity of Alexander's "Rat Park" experiment has been disputed. Some further experiments have replicated it and some haven't, although the latter were performed under different conditions. Still, Alexander found the same effect with alcoholism in Native American populations, among other historical examples.

More importantly, Portugal actually decriminalized all drugs in 2001 and its "drug situation has improved significantly in several key areas. Most notably, HIV infections and drug-related deaths have decreased, while the dramatic rise in use feared by some has failed to materialise." Heroin use fell to about half of its late-1990s level. So it should come as no surprise that many are suggesting that we take the same approach in the United States.

3. "The death penalty deters murder."

It seems like common sense that the threat of being killed would stop someone from killing. Some studies has appeared to back this up, finding a relationship between capital punishment and lower crime. However, as soon as other variables (e.g. incarceration rates, life sentences, which homicides are eligible for the death penalty, etc.) were taken into account, the deterrence effect disappeared. A sizeable body of research has supported that murders – which are often committed in the heat of the moment rather than premeditated – are not deterred by capital punishment.

On critical examination, even the "common sense" idea does not make sense in real life. Murders are frequently not premeditated, so criminals would not take the consequences into consideration. Even if they did, why would they think that they would end up with the death penalty considering how sparingly it is applied in modern times?

Ultimately, all three of these are flawed policies that should be changed if not repealed – the sooner the better.