In an age when disease, mishaps, and overall despair are unfortunately all too common, people may lose their judgement as to who/what they should trust when they read it. Scientific discoveries are a category often plagued by bad science, whether it is misunderstanding a legitimate discovery or study, or it is just simply false altogether. Here are several ways to determine whether or not a source should be trusted as scientifically correct.

Signs of bias.

Neil DeGrasse Tyson once said, "Science works whether you believe in it or not." This holds true for trying to determine whether or not a site has a potential conflict of interest. Sites like Truthkings, Collective Evolution, and Infowars harbor an anti-establishment agenda and, therefore, classify science as part of the "conspiracy" they are fighting against. This is also true for any signs of political bias, as well.

It's too good to be true.

Reading something like, "Lemons cure cancer" should be a red flag. Such a statement only chips off a snowflake of the science behind it, leading on to the next point.

Grossly misinterpreting a study.

Again, to the lemon example above, the actual study found that a certain isolated compound found naturally in lemon peels has an inhibitory effect on the development of malignant tumors. However, this does not mean that lemons cure cancer because we do not yet understand the dosage and other factors related to the pharmacological effect of that specific compound.

No credible studies cited.

Any credible site that makes claims regarding to science should have references to articles published in peer-reviewed journals that are widely accepted by the scientific community. If it is in a science database found in your school library, then chances are, it is credible.

Circular references.

If you browse sites such as Natural News, Infowars (I don't know why you would when you could be reading credible, peer-reviewed journals), you will realize that these sites cite each other as sources in many articles. Rather than discussing one particular piece of evidence, these two pieces of "evidence" are each others' only proof.

Marketing attempts.

Many anti-science sites (anti-vaccine, anti-GMO, anti-pharma, etc.) will attempt to peddle supplements and other items claimed to have health benefits. Not only are these supplementary materials unproven, they can be potentially dangerous. Sites such as these often make customers from the propaganda they publish.

Allusions to conspiracy theories.

This should be a no-brainer, but to reiterate, the feasibility and longevity of a conspiracy is inversely proportional to the number of individuals involved. For example, Edward Snowden was one of 30,000 NSA employees who were involved in a public surveillance scandal. It only took one out of 30,000 to bring this issue to light. Imagine how easy it would be to reveal a conspiracy involving every scientist on Earth.

Fear mongering.

The use of rhetoric or images to invoke fear should be evidence that this piece is not credible. Why would such fear be needed if overwhelming evidence to back it exists?

Appeal to nature, emotion, ancient wisdom, etc.

If you see an article on how to do something the natural way, the ancient Chinese way or a similar headline then, chances are, it is not grounded in modern scientific evidence.

Misuse of buzz words.

If any such word is thrown around liberally, the author may have a poor understanding of it. The most common offenders are "toxins,""chemicals," "inflammation," "body pH," and "GMO."

Science that you know to be false, based on your professional involvement.

If you know something to be false based on academic or professional experience, by all means avoid it. Chances are, your course credits from an accredited institution hold more water than information from Google University.

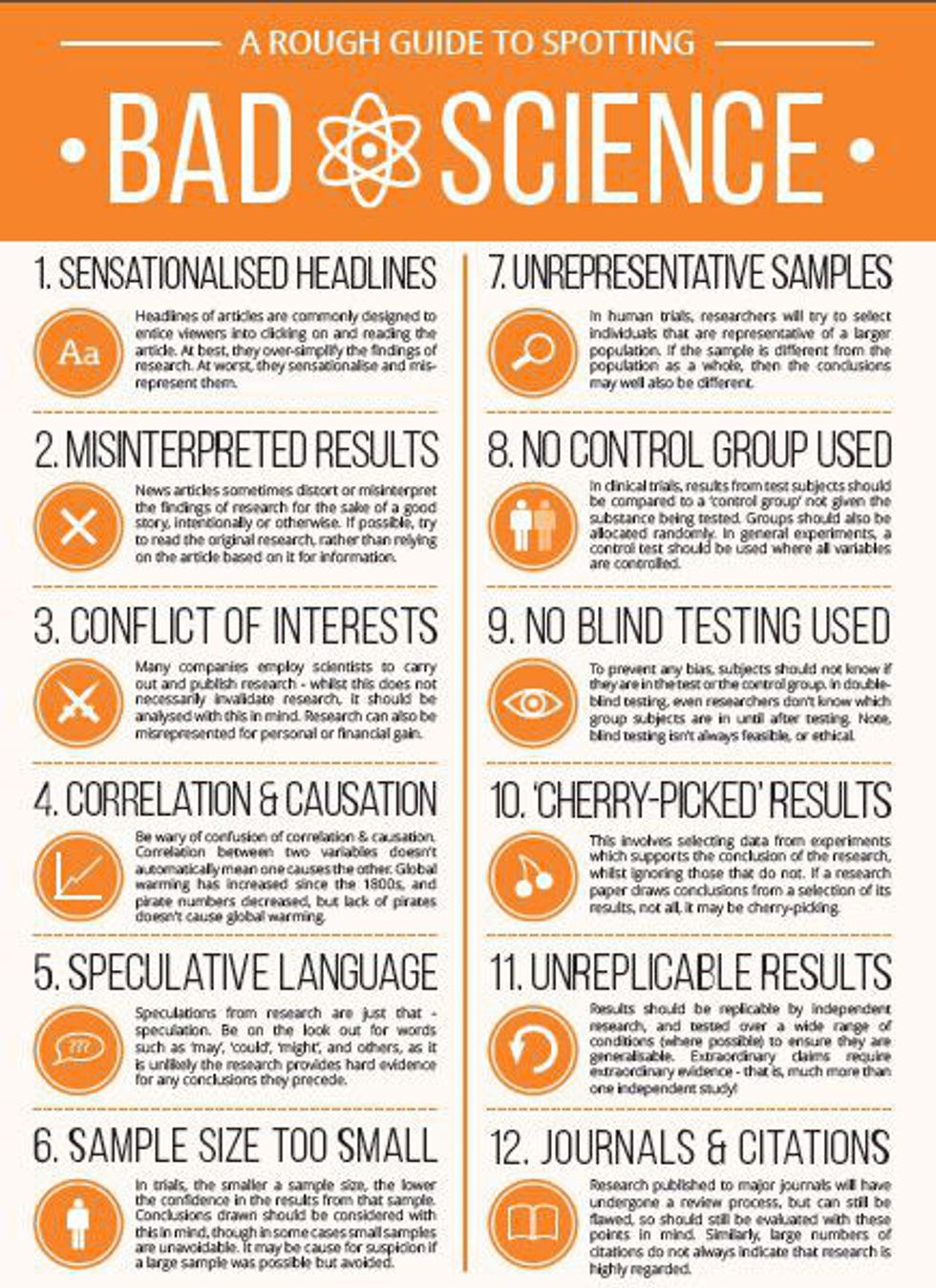

It fits one of these categories:

(Image credit: Pinterest)

The list of red flags could be longer than Encyclopedia Britannica, but if it fits one of these categories, the article might be dubious in trustworthiness.

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by