“Here’s to strong women”, the old feminist quote reads. “May we know them, may we be them, may we raise them.” It’s a statement that often evokes pride in the hearts of feminists everywhere as images of feminist icons who came before us are brought to the forefront of our minds. Images of Susan B. Anthony fighting for women’s suffrage, Gloria Steinem creating Ms. Magazine to give women’s issues a platform, and even Hillary Clinton becoming the first female Presidential candidate for a major political party often inspire us to show our daughters what it means to be a strong woman. And while these women are truly strong and powerful women who contributed to the feminist movement in fantastic ways, with solely these images we continue a long standing cycle filled with “this is what a feminist looks like” t-shirts on white bodies that for so long have been the major face of women’s rights, while many young girls of color are left without representation within a movement supposedly meant to represent them as well. Unfortunately, much like President Trump’s Black History Month speech, the contributions of many black feminists to the feminist movement have long been overlooked and replaced with an overwhelmingly white narrative due to an unwillingness from the movement to understand that while women of color are affected by sexism, as is every woman in a patriarchal society, black women and other women of color must also deal with a systematic racism that many white women will rarely, if ever, face in the United States. While feminism has made long strides since its inception in attempting to become much more intersectional, a term coined by black feminist Kimberle Crenshaw, we still have a long way to go before we are truly as inclusive and diverse as the women who make up this country. Until the contributions of black feminists are just as celebrated and recognizable as those of our white feminist icons, we cannot call ourselves a movement of the people. So in honor of Black History Month, here’s to the powerful black feminists who have contributed and/or still contribute largely to women’s rights and the feminist movement, but are too often overlooked. May we finally know them, may we be them, and may we raise a new generation of black feminists to know that they too, are what a feminist looks like.

1. Sojourner Truth

Born into slavery as Isabella Baumfree, Sojourner Truth escaped slavery with her youngest daughter in 1826, where she would soon become one of the most recognizable faces of the Abolitionist and Women’s Rights Movement. After her escape, Truth was one of the first black women to successfully challenge a white man in court after she discovered her former slave owner had illegally sold her five year old son to another man. After rescuing her son, she soon worked alongside abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas for both the freedom of slaves and women’s suffrage. Truth focused most of her energy on the plight of black women who were often ignored in the women’s suffrage movement and who she feared abolitionists would forget after black men received their freedom and the right to vote. It was in 1851 at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron where Truth would deliver her now famous speech “Ain’t I A Woman?” that discussed the hypocrisy of so called “male chivalry” that was used as an excuse to keep women from voting. She pointed out that while men claimed that women were delicate and needed to be given special care due to their so called nature, she was never offered such courtesies and was strong, not “delicate”, and yet was still considered a woman. This pointed out that not only were black women treated less courteously than white women were in terms of “chivalry”, but that the idea that women’s very nature was a delicate one was nonsense because she was clearly a woman from her ability to bear children and cry with a mother’s grief over their loss, yet was as strong as any man.

In 1872, Truth attempted illegally cast a ballot at a local polling station but was turned away in Battle Creek, Michigan. She would later die in Battle Creek, Michigan on November 26, 1883.

2. Alice Walker

Born February 9, 1944 to Georgia sharecroppers, Walker grew to become a writer and an activist that helped to define the Black Feminist Movement during its inception, a movement that would later be called Womanism, a definition created by Walker in her essay “In Search of Our Mother’s Garden” as a reaction to a feminism that did not apply to or take black women into consideration. Walker defined Womanism as:

"Womanist 1. From womanish. (opp. of "girlish," i.e., frivolous,irresponsible, not serious.) A black feminist or feminist of color...Usually referring to outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful behavior. Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered"good" for one... Responsible. In charge. Serious.

2. Also: A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually. Appreciates and prefers women's culture, women's emotional flexibility(values tears as natural counterbalance of laughter), and women's strength... Committed to the survival and wholeness of entire people,male and female. Not separatist, except periodically, for health. Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender."

She is best known for her novel The Color Purple, a book about overcoming the overwhelming racism and misogyny enforced by the culture of the South and would continue to use many of her novels and poems to address social justice issues such as sexism and racism as well as rape and violence.

3. Angela Davis

Born January 26, 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama, Angela Davis grew up seeing how racism affected black lives as she knew some of the girls who were killed by the KKK in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing. She would later become a part of the black feminist movement as an activist and a scholar, writing the book Women, Race and Class to highlight the role that gender, skin color and social status played in the women’s movement and allowed racism to breed within it. Davis has been associated with the Black Panther Party as well as the all black branch of the Communist Party known as Che-Lumumba Club, as she is a strong believer that capitalism and democracy could never serve people of color due to these systems being set for white males to continuously hold power over others, disguised as the choice of the people. She would later serve time as a political prisoner when she was suspected of being apart of the attempted prison breakout of the Soledad brothers, all of whom were members of the Black Panther Party. She would later be acquitted of all charges. She is now a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz and continues to be an activist for intersectional feminism and for Palestinian freedom.

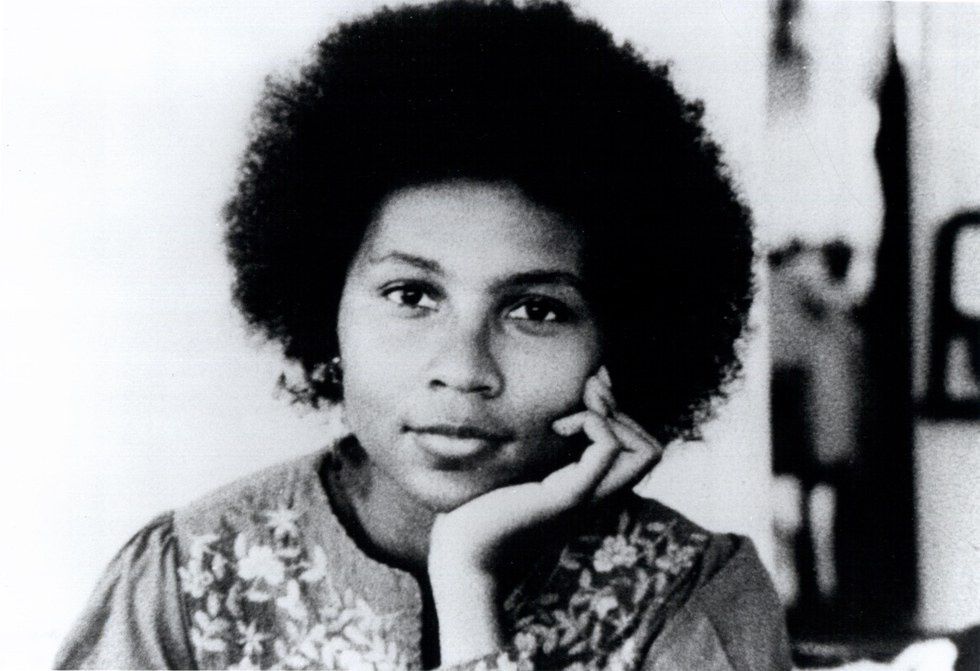

4. bell hooks

Born in the South during segregation on September 25, 1952, Gloria Watson, who later changed her name to bell hooks, grew to become an academic and writer of countless works, including writing that would help to mold the Black Feminist Movement. hooks often focused her writings on the perceptions of black women and spoke out against patriarchal standards within the Black Liberation Movement that were often used to control the sexuality of the women within the movement. Although initially met with resistance at pointing out the sexism within the Black Liberation Movement as well as the racism found in the feminist movement, hooks’ writing in Feminist Theory From Margin To Center pushed the idea that feminist theory needed to be more accessible to women of color. She is well known for standing for not only harmony between races and economic classes within Feminism, but also for harmony between genders as she believes that it is essential that men help to expose and transform sexism in society. hooks has also used her writing to change the perception of black female intellectualism and is now a professor at Berea College.

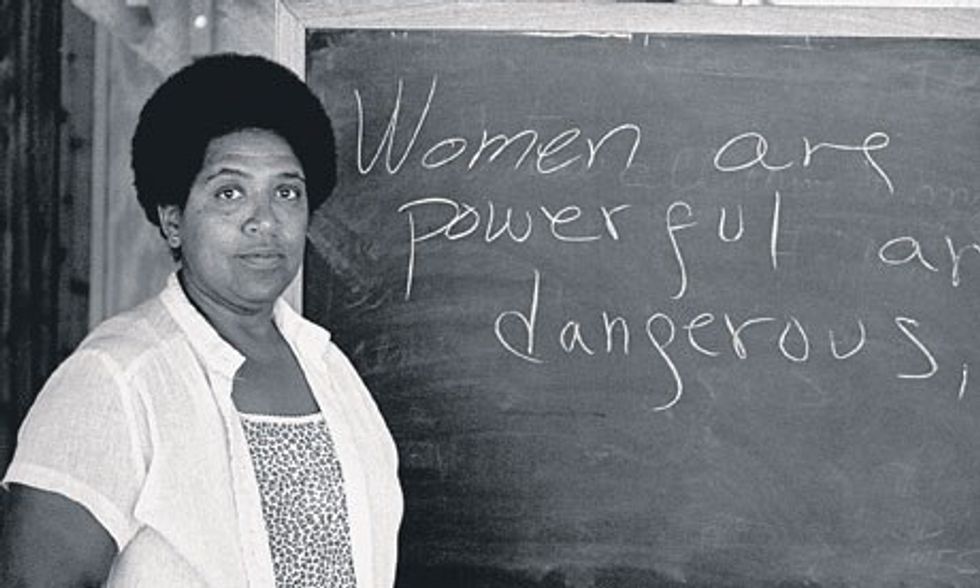

5. Audre Lorde

Born February 18, 1934, in New York City, Lorde added to the conversation of intersectionality in the feminism by challenging heteronormativity and homophobia within the movement as well as bringing attention to how labels such as race, gender and sexuality create a system of marginalization for groups that do not fit a particular “norm”. She used her poetry to address issues such as class, race, heritage, family, and even her own sexuality in the poem Martha. After being diagnosed with cancer, Lorde moved to the US Virgin Islands where she took the African name Gamba Adisa, as well as released her nonfiction essays known as The Cancer Journals, in which she confronted her struggles with her illness. She died on November 17, 1992 and is remembered for her contributions to intersectional feminism and political activism through her writings.

6. Kimberle Crenshaw

Born in Canton, Ohio in 1959, Crenshaw made a lasting mark on the feminist movement when she coined the term “intersectionality” in her 1989 essay Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, finally creating a word for the ways that black women and women who do not fit what are often perceived as “norms” in other categories such as sexuality and ability experience oppression. The legal scholar used the analogy of an intersection in traffic to help explain how these issues cross and function as a whole. She stated:

Her work with race and gender was influential in the writing of the South African constitution as well as many other global initiatives for women’s rights. She is the co-founder of the African American Policy Forum as well as a professor for UCLA School of Law and Columbia Law School specializing in race and gender issues.

7. Moya Bailey

Although Kimberle Crenshaw created a term that would describe the different types of struggles that contribute to the oppression of women from race to class, Moya Bailey contributed to the black feminist movement by creating a term that was specific for anti-black misogyny known as misogynoir. In her essay known as the Crunk Feminist Collective, Bailey, who is a black queer legal scholar, described misogynoir as “the particular brand of hatred directed at Black women in American visual and popular culture,” and described the hatred as being capable of transcending both intraracial and interracial relations with black women due to the American public’s negative portrayal of black womanhood. Bailey wanted to show that this particular hatred was unique to a black female perspective due to black women often being denied an idea of “womanhood” that has been built by eurocentric patriarchal standards of femininity. Bailey is currently a digital alchemist for the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network and uses her work in digital media for the social justice of marginalized groups.

8. Ava DuVernay

The director of the civil rights film Selma has been a vocal advocate for not only women’s rights, but also for the inclusion of black women and minorities in media. The first black female to direct a film with a $100 million budget, DuVernay runs AFFRM + Array which is a distribution company that supports black independent films and films made by up and coming directors for people of color. She has brought attention to the effects of both racism and sexism in media representation as well as black women’s ability to find work in Hollywood weather it is behind or in front of the camera. At the 22nd Annual Elle Women In Hollywood Awards, DuVernay stated:

DuVernay is currently directing the film A Wrinkle In Time.

9. Amandla Stenberg

Born on October 23, 1998 in Los Angeles, the actress best known for her breakout role as Rue in The Hunger Games has been an outspoken activist who represents a new generation of black feminists. After posting her 2015 school project “Dont Cash Crop My Cornrows”, a video discussing the cultural appropriation of black culture by white society, Stenberg began speaking out as an intersectional feminist to attempt to shed light on issues that oppress black women in a eurocentric world. In a mini-essay, Stenberg discussed how “...white women are praised for altering their bodies, plumping their lips and tanning their skin, black women are shamed although the same features exist on them naturally." She has been praised by Solange Knowles as well as Gloria Steinem for bringing in a new generation of young women to feminism as well as shining a light on issues that affect black women and culture.�She has stated she wishes to study film making due to the lack of “powerful and nuanced representation for women of color” in the media.

10. Shirley Chisholm

Well before Hillary Clinton was applauded for smashing the glass ceiling during the 2016 election, Shirley Chisholm was putting some of the first cracks in the glass ceiling when she was not only the first black woman to seek a Presidential nomination in 1972, but also the first woman EVER to have her name placed on a Presidential ballot. Born in Brooklyn in 1924, Chisholm would go on to become the first black woman to be elected to Congress when she represented New York’s 12th District for three years. After serving in Congress, she decided to place her name on the ballot to campaign for the Democratic nomination for the Presidential election. Her announcement to run went as follows:

I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud.

I am not the candidate of any political bosses or fat cats or special interests.

Thank you ladies!