Listicles: they're widespread and readily accessible - the same could be said of The Plague circa 1347 CE. In my research for this piece, every article (or rather, I should say 'listicle' as they all were all formatted in this manner) began with a resounding promotion of either of these qualities, or in one case, a mocking admonishment for those too pedestrian to have happened upon this, the Holy Grail of disseminating information. Listicles are not nearly as benign as their oftentimes shallow, vapid content might suggest, rather the style possesses certain qualities - devilishly clever devices that subvert our limited senses to install potentially damaging methods of processing and comprehending information.

1. Empty claims masquerading as authorities

http://thestaticstalker.deviantart.com/art/GIF-gif...

"7 Things Dogs Do That Prove They Really, Really Love You", a listicle hosted by a website known as The Dodo, does little in the way of converting its readers to harmful ideologies. It's a short list, containing less than ten or so points about behavioral cues our canine companions really, really love us; seemingly innocuous proclamations to be sure - I learned that a dog might wiggle its eyebrows when it sees its owner, for example. I even found myself sharing that bit of information in passing small talk with coworkers, not particularly engaging with this fact. Why should I, or rather why would it occur to me to do so? The information was not in difficult territory, a topic far from the relatively agreed upon danger zones of religion, politics, and sex. I saw no reason to doubt the veracity of the claim, which made it all the easier for me to idly pass along as verified fact.

Weeks later, I jokingly suggested to my editor that I ought to write a listicle about listicles. Still only barely serious, I went navigating through list after list only to happen on this mundane click-bait shrug-piece on puppies and love. Upon further review, I rediscovered that fact that I had so blithely shared, only to be reminded that the truth was more specific. Rather than wiggle their eyebrows like the numbered sub-headline suggested, rather the validating link apparently indicated that "...the results showed that dogs raised their eyebrows when they saw their owners, but not when strangers walked in." according to the small paragraph beneath the picture of an adorably goofy dog's face. Realizing my mistake, I figured that I should actually read the study so that I would avoid making the same unintentional error again - only to discover that the author of The Dodo lisitcle had made a similar slip. The abstract for the study hosted by Science Direct reads thus:

"...The dogs’ facial expressions were recorded by a high-speed video camera during the presentation of emotional stimuli and the acceleration rates of parts of their faces were analyzed. The results showed that the left eyebrow moved more when the owner was present than at baseline. No bias in terms of eyebrow movement was observed when the dogs saw attractive toys. These results suggest that dogs show facial laterality in response to emotional stimuli. This laterality was specific to social stimuli, probably reflecting the dog's attachment to the owner."

Moving away from the emerging trend toward deepening source complexity (I'll spare you the definition of "emotional laterization" and its subsequent theories and implications), I think this highlights a troubling flaw. A list is a streamlined and ethically neutral method of portraying a set of information that would otherwise be riddled with subjectivity and far too detailed for a layperson to comprehend, let along make use of. What the author of the listicle in question is asserting by assuming her reductionist role is that we the readers should trust her to accurately portray the information she had gleaned from researching this topic. What becomes clear from following up on this claim is that it is not only false, it has been whittled into a new shape that fits the article's narrative. In reading this listicle, we're not expected to consider the complexity of the human/canine relationship that has been cultivated over thousands of years of domestication. Nor are we supposed to ponder the ideal of love or a dog's ability to feel or express an anthropomorphic emotion. The style suggests an authority and an integrity that is undermined by the author - and for what purpose?

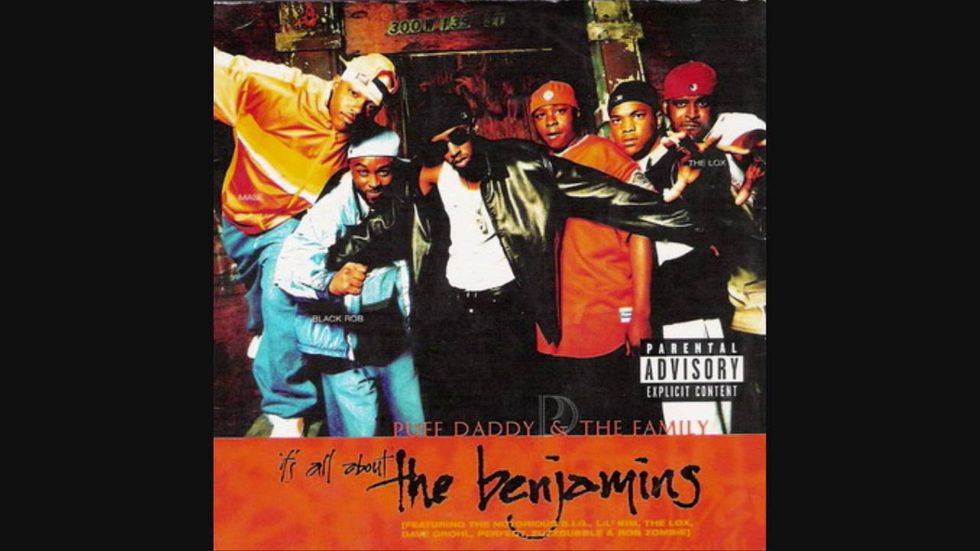

As the great poet Puff Daddy puts it in his album No Way Out, "It's All About the Benjamins" - more views in this Internet economy translates to more money for the host sites. These tactics, including equating 'likes' on social media with social acceptance, appeals from intentionally misrepresented authorities, and more are meant to optimize our time spent on their sites via manipulating the way we think about both ourselves and the world we live in.

Nicholas Carr describes our minds' ability to change and its relationship with the Internet in his article for The Atlantic titled "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" -

"The human brain is almost infinitely malleable. People used to think that our mental meshwork, the dense connections formed among the 100 billion or so neurons inside our skulls, was largely fixed by the time we reached adulthood. But brain researchers have discovered that that’s not the case. James Olds, a professor of neuroscience who directs the Krasnow Institute for Advanced Study at George Mason University, says that even the adult mind “is very plastic.” Nerve cells routinely break old connections and form new ones. “The brain,” according to Olds, “has the ability to reprogram itself on the fly, altering the way it functions.”

Carr goes on to cite how past innovations have altered our very perception of time:

"As we use what the sociologist Daniel Bell has called our “intellectual technologies”—the tools that extend our mental rather than our physical capacities—we inevitably begin to take on the qualities of those technologies. The mechanical clock, which came into common use in the 14th century, provides a compelling example. In Technics and Civilization, the historian and cultural critic Lewis Mumford described how the clock “disassociated time from human events and helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences.” The “abstract framework of divided time” became “the point of reference for both action and thought.”

This is all relevant to us because of the dangerous trend of sharing data that carries factual weight, regardless of its actual validity. The concepts of "fake news", "alternative facts" - we are assaulted by so much information on a day-to-day basis that these notions appeal, reflecting the metadata mined and tailored to fit headlines that appear in our social media news feeds. The very structure of the Internet has been molded to target our vulnerabilities; serving our primitive vices instantly in exchange for more data, always more so they can better calibrate the machine to extract yet still more.

Given these phenomena's ability to subvert elections and shape entire ideologies, I'll leave it to you to consider how dark this ride may get if these trends continue. The near-infinite capacity for our minds to adapt and conform to new technologies is arguably the most useful and successful tool we possess as a species; a tool turned against us to benefit an industry that profits from keeping us misinformed and satisfied with what we supposedly know.

The manipulation manifests in more than simple puppy love - consider what else could be slipping through the cracks. Even a second, passing glance may reveal an attempted or even successful hijacking of our limited faculties.