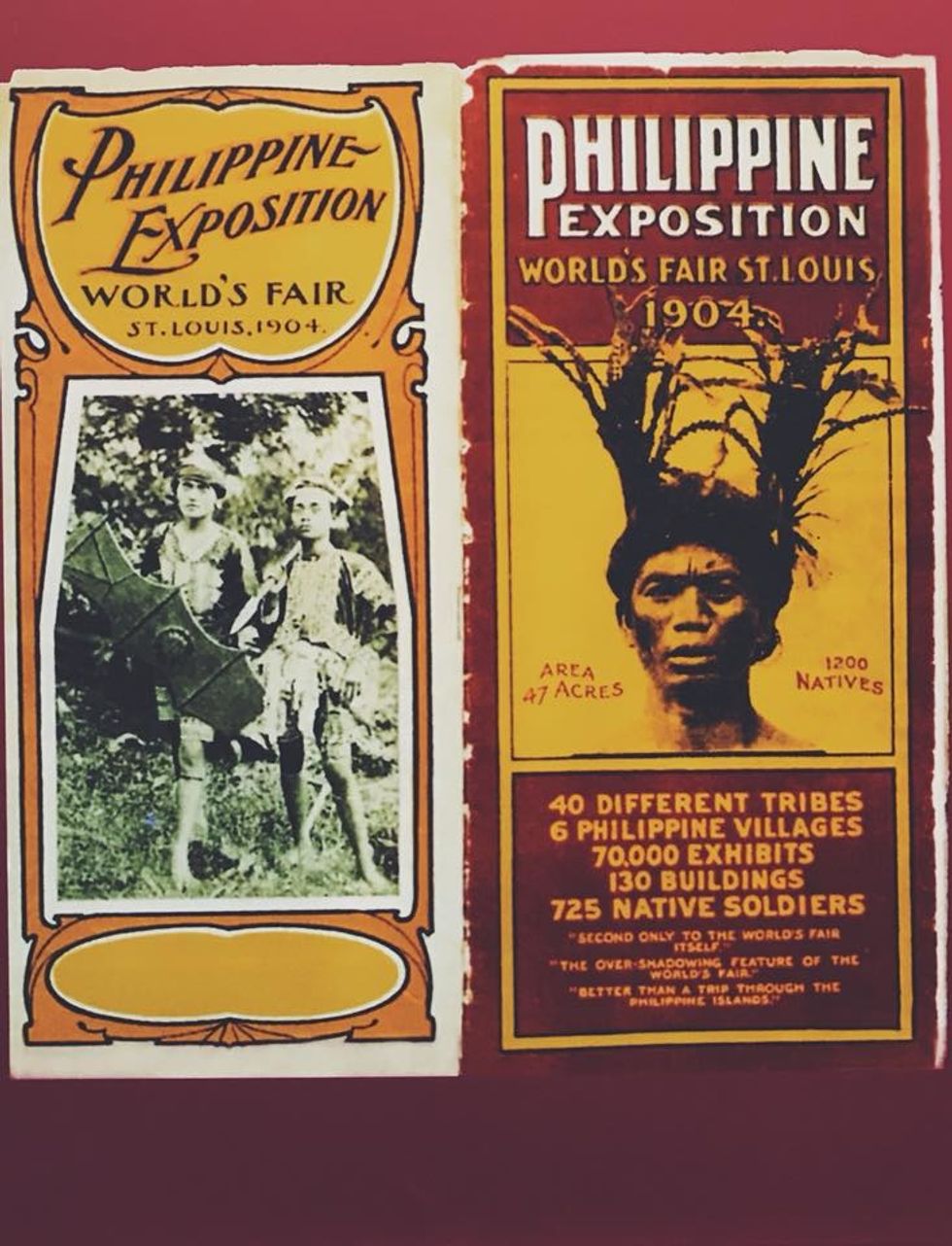

White. White. White. White kings, white queens, white scandals, and white colonies. There is a sprinkle of Black slavery, Hispanic territories, and Native American displacement. There is a short paragraph on Chinese railroad workers, a narrative making Japan out as the WW2 bad guy, and a two-liner on the refugees of Vietnam. And there is, for the benefit of my people, one line about the Philippine-American War.

I loved history because of its storytelling narrative, but as I learn in my college education, I have been robbed of a history that is very much American and a lot more relatable and personal to my narrative than what I learned in U.S. history. It took me 19 years to find this voice as, not just a Filipino, but a Filipino-American.

They were called manongs. In the standard contexts, the Filipino word signifies respect for an older family relative. In the context of the Filipino-American experience, it refers to the Filipino immigrants in northern and central California that started it all.

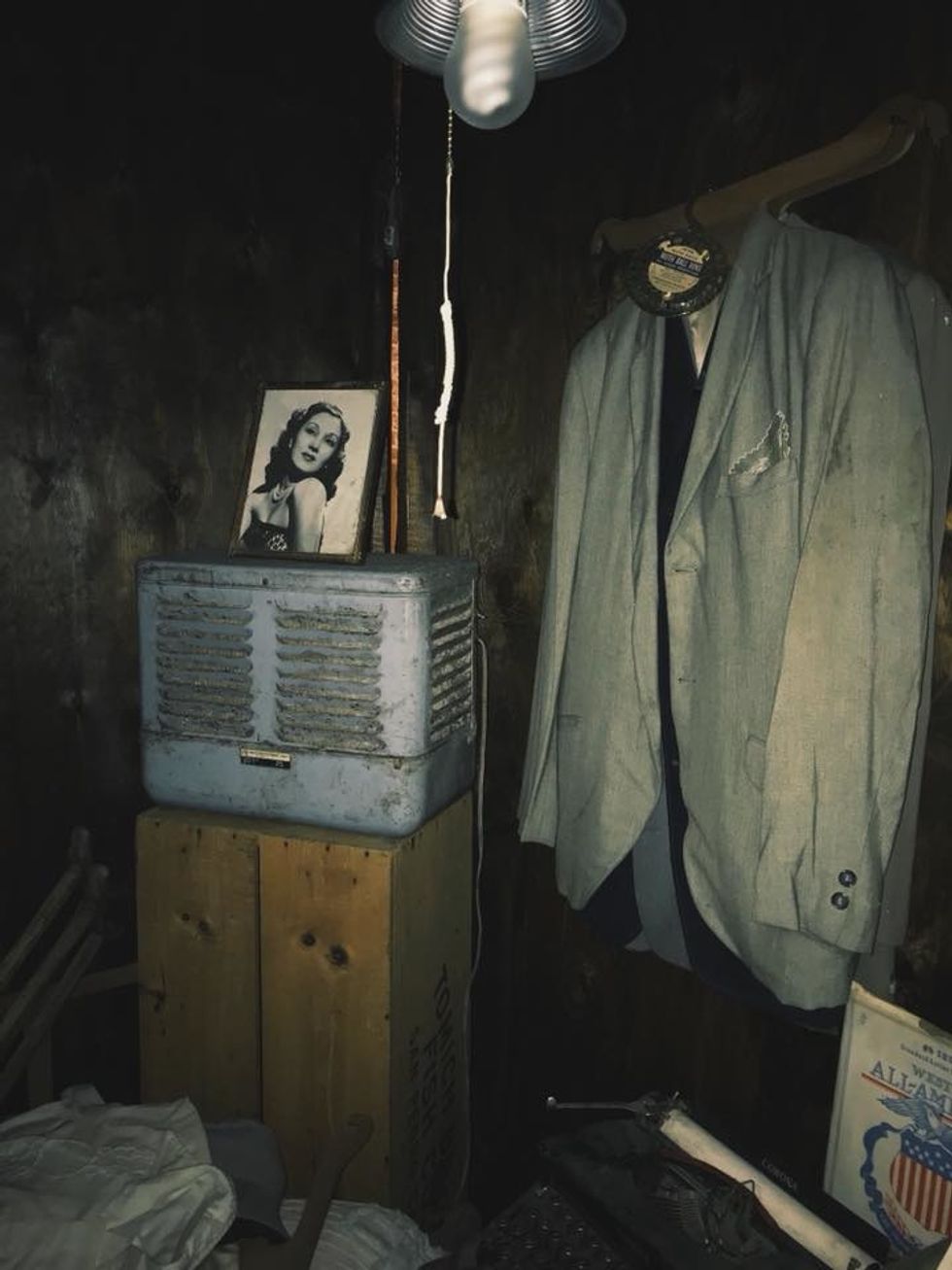

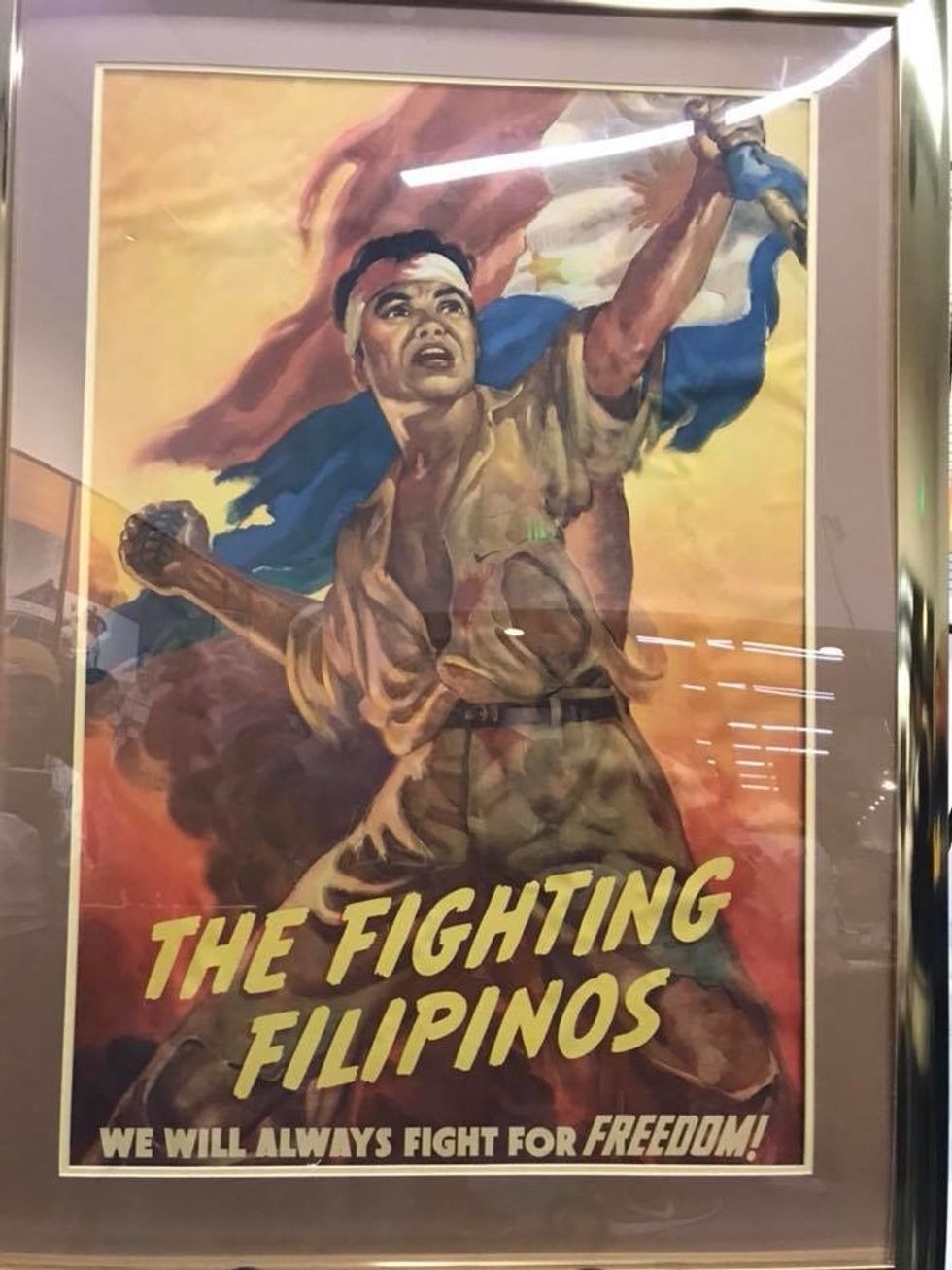

A little of a history lesson: during the 1920s and 30s, a wave of immigrants from the Philippines continent moved to the United States. Filipinos immigrated and concentrated in Stockton, California. Stockton was chosen for its proximity to the farms that the immigrants worked in and the dense Filipino population that had already made a home for themselves in Little Manila. In his 1943 semi-autobiographical novel America is in the Heart, Carlos Bulosan arrives at Stockton on a bus and writes "...familiar signs glowed in the coming night... I saw many Filipinos in magnificent suits...there must have been hundreds in the street somewhere..I walked eagerly among them, looking into every face and hoping to see a familiar one." His novel elaborates on the illusion of the American dream, the harsh realities of poverty and discrimination these manongs were forced to face, and the suffering of Filipinos against policemen, employers, white men, white women, and America itself.

I recall the hot tears that sprang in my eyes reading about the hardships Bulosan faced.

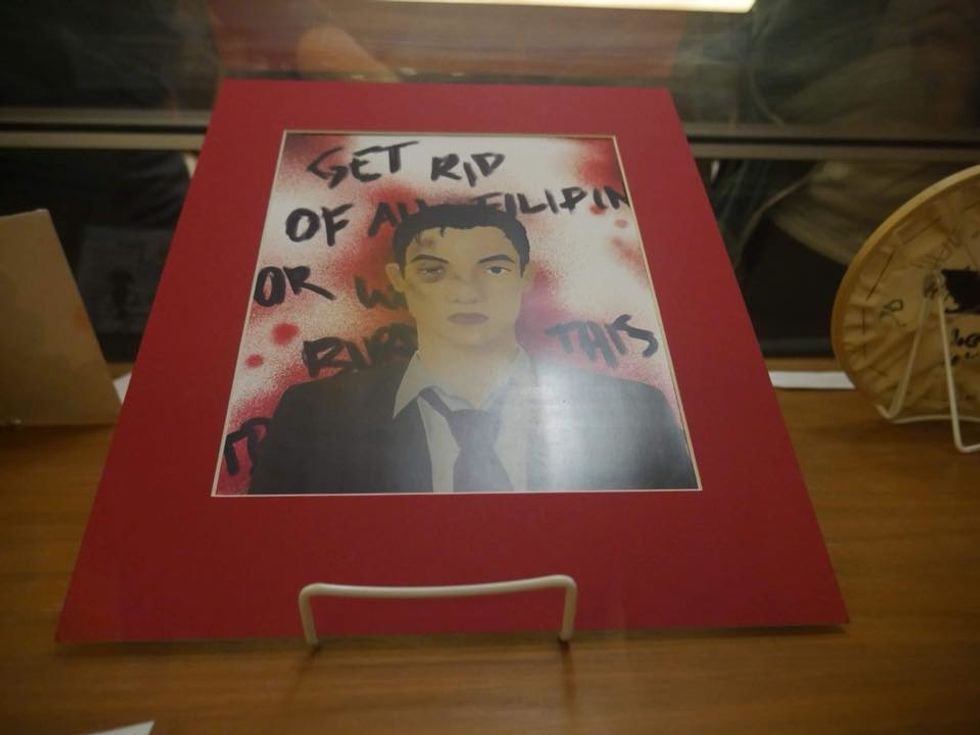

I remember vividly the anger rushing through my veins as I sat in my Asian American studies class, learning about laws against early Asian immigrants. Most of all, I recall the solemn sadness and heartbreak I felt, standing on the sidewalks of Stockton, grasping at what it must have felt like to be bloodied and beaten on the floor for dancing with white women in a rented out "taxi dance hall." As I stare at a white, dilapidated building, I am struck with a heavy hand at the image of Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz in those rooms, mapping out the United Farmworker Association's grape strike and their painstaking deliberation that is forgotten from the Cesar Chavez biography. I just can't help but think how much we have been erased, and in a possible case, erased ourselves, from the American narrative.

Even if I tried when I was younger, this history was not accessible to me because my recently-migrated family does not know about it, either. Our first roots in America started in the 90s, decades after the manongs. There was no sense of knowing that I had roots as a Filipino-American and can claim a connection to American history.

Is this what being white feels like, learning about the colonies and democratic government in a formal classroom? Seeing your skin and your history reflected on textbooks and portraits around the country? I cannot fully relate to U.S. history or history in the Philippines, because I am neither American nor Filipino. I am both, a Filipino-American, and my history has been robbed from me. My identification with my culture and environment have been taken from me. My understanding of those who have come before me have been erased, and so I, too, have been erased. Because, how can I truly know my capacity for strength, perseverance, and power in the context of this American society if I didn't even know it existed?

The Filipino American experience is still under full investigation and the academia surrounding it turns up new information every day (Did you know the first female doctor graduate from Harvard was a Filipina woman?). Filipino organizations try to keep our history alive through classes and workshops in the community and attempt to shed light on our forgotten histories. This passion, for many, comes from finding justice for the manongs nearly forgotten about.

The community is putting pencil to paper, putting history to heart, in order to bolden our already-existing narrative in the "land of opportunity."

- You Should Watch 'On The Wings Of Love' Over Your Holiday Break ›

- Ethnic Studies Should Be A Required Course In Schools ›

- Historical and Cultural Connections Between Indonesia and the ... ›

- Dear Filipinos: We're Not Latino, We're Southeast Asian, Get Over It ›

- Yes, I'm Filipino But That Doesn't Mean I'm a Nurse. ›

- If You Understand These 30 Things, You're Probably Filipino ›

- In Honor Of Filipino American History Month, Here Are 7 Facts You ... ›

- 11 Facts In Honor Of Filipino-American History Month ›

- October Is Filipino American History Month ›

- Filipino Immigrants in the United States | migrationpolicy.org ›

- This Week Then: Celebrating Filipino American History Month in ... ›

- 120 years after Philippine independence from Spain, Hispanic ... ›

- Filipino Americans : Asian-Nation :: Asian American History ... ›

- 15 Memorable Facts About Filipino-American History You Should ... ›

- The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902 ›

- Filipino American National Historical Society: FANHS ›

- Filipino Americans - Wikipedia ›

- 8 Dark Chapters of Filipino-American History We Rarely Talk About ›

- History of Filipino Americans - Wikipedia ›