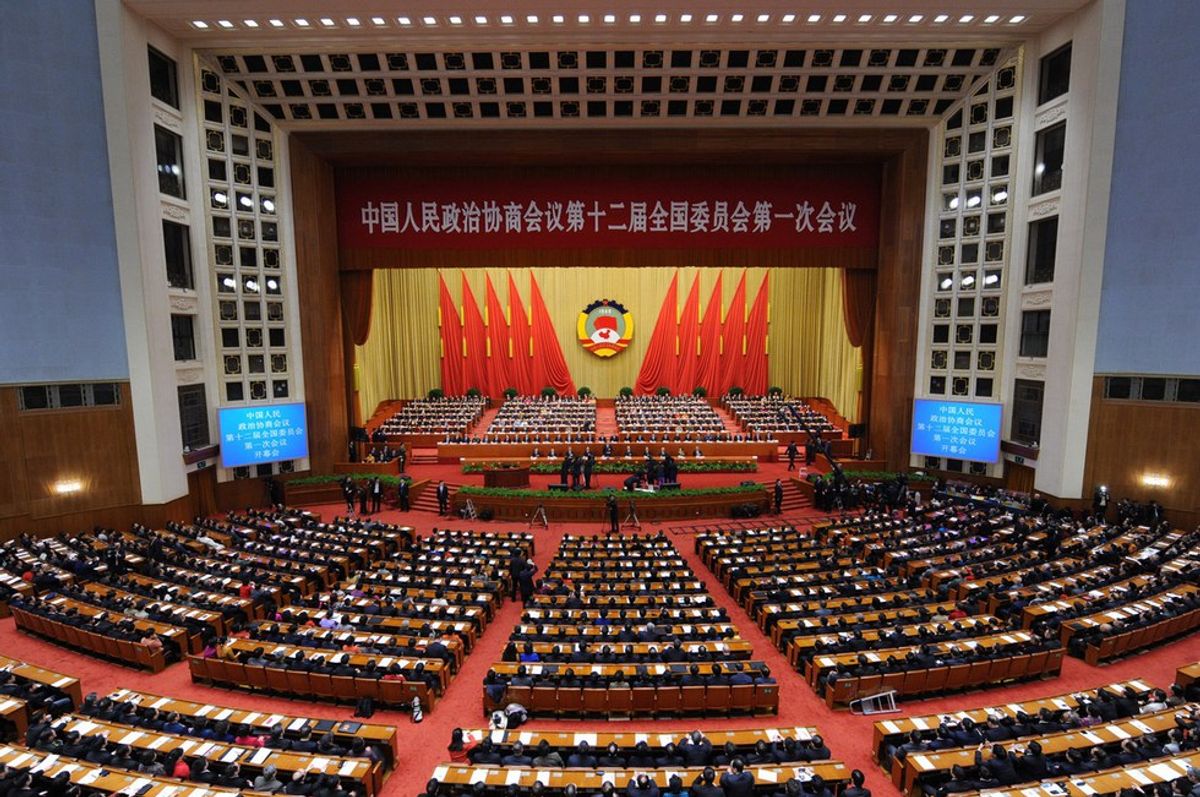

In 1957, Chairman Mao Zedong proclaimed "Not to have a correct political orientation is like not having a soul." There has been much written on the extreme, frequently violent efforts made in Maoist China with the intention of creating a unified national ideology. Mao partially justified his brutal suppression of the free speech and thought of dissidents with the Leninist concept of democratic centralism: the idea that everyone within the ruling party should stick to a position once debate on it has been settled. As Lenin himself put it: "Freedom of discussion, unity of action." The term "democratic centralism" appeared in the original 1954 Chinese Constitution, and remains in today's version. Both Constitutions also refer to China as a "people's democratic dictatorship." And yet, despite these apparent similarities with the past, China today is certainly not the same as it was under Mao.

Ever since the late 1970s and 1980s, China has become a dramatically different place, one that can no longer be accurately called "socialist" or "communist" at all. Driven by Former Chairman Deng Xiaoping, China began a period of extensive economic liberalization, loosening state control over the economy, permitting private industry to play a significant role, and expanding the role of the market. This economic liberalization, however, was not met with political liberalization. Deng stated that the Chinese government "should introduce to our people, and particularly to our youth, whatever is progressive and useful in the capitalist countries, and we should criticize whatever is reactionary and decadent." He sought to promote "a political situation in which we have both centralism and democracy," instead of the "bourgeois" and "individualist democracy" seen in the West. In reality, this meant maintaining state control over politics.

The infamous 1989 massacre of protesters at Tiananmen Square served as an illustration of the basic guiding principle of the new post-Mao China: liberal economy, illiberal government. As Journalist Evan Osnos puts it in his book, "Age of Ambition," the Chinese government "shed its scripture but held fast to its saints; it abandoned Marx's theories but retained Mao's portrait on the Gate of Heavenly Peace, peering down on Tiananmen Square." In the name of Mao, it was announced that a unique form of capitalism was coming to China.

State propaganda and restrictions on speech are still ever-present features of modern China, but they have become much more subtle and less openly coercive. This, combined with globalization and the reforms of the 70s and 80s, have lead to a situation where there is much more freedom of speech and thought than there was previously, allowing people to express themselves in new ways. This freedom has given rise to a new opportunity for researchers: gauging what Chinese citizens actually believe about politics.

Jennifer Pan of Harvard University and Yiqing Xu of MIT released a study titled "China's Ideological Spectrum," which looks at more than 460,000 responses to a "Chinese Political Compass" quiz online. The aggregate results of the quiz are available for those who are interested, but the study asks a different question: does the diversity in political opinion among Chinese people form an ideological spectrum, similar to America's liberal-conservative spectrum?

Pan and Xu found that it does: "We identify an ideological spectrum in China—one dominant ideological dimension where preferences on political, economic, and social/cultural values are highly correlated." Along this spectrum, "The majority of respondents are located in the middle... rather than at the ends." Additional commentary on their findings, which is most often quoted from in this article, can be found in an earlier draft of the paper.

What is fascinating, however, is that the spectrum of Chinese opinion is distinctly different from that in most Western nations. The study identifies two groups on each end of the spectrum of Chinese thought. "Conservatives" favor "nationalism, a strong and powerful state, big government, Chinese identity, and cultural conservatism," while "liberals" favor a "constitutional democracy," "protection of individual liberties" and "promotion of a free market economy." A fuller explanation appears in chart form:

Different Definitions

At first, these labels may seem to make no sense: why are "conservatives" considered left-wing and "liberals" considered right-wing? We associate conservatives with national security and traditional values, but not socialism or welfare. On the other hand, liberals are associated with civil liberties and human rights, but not with the free market. These confusions stem from our own myopic views. We think of these terms in the contexts in which their presently viewed here in America, and ignore the ways that ideologies vary by time and location.

Originally, the term "liberal" was given to Enlightenment-era thinkers who supported the form of liberalism described above to varying degrees. This is why we still use the term "liberalizing" which means "loosening government control over." The term "liberal" only began to take on its current definition (social and cultural permissiveness combined with welfare state economics) in the late 19th and early 20th century. Modern-day returns to classical liberalism based around free trade, low regulation and taxes, and privatization are frequently referred to as "neoliberalism."

In the same way, "conservative" originally referred to those who supported social and political hierarchies while opposing radical changes in society. Such an ideology is fully compatible with the idea of a welfare state, as a welfare state can help promote social stability. In fact, the first modern versions of the welfare state were developed by two prominent 19th century conservatives: German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. Some variation of this type of conservatism can still be seen in many places around the world, but it has become far less popular over time. The term "conservative" currently refers to a fusion of both traditional conservative thought and classically liberal views, resulting in a belief in both traditional values and laissez-faire economics.

Knowing this history, the context of Chinese politics makes much more sense. Modern Chinese thought is now split between "conservatives" and "liberals," two groups which share similarities with those of the same labels that existed long ago in the West. The study points out that the reason for China's alternative spectrum is influenced by the fact that they start their arguments without the preconceived notions about the benefits of liberal democracy that many Westerners have. Americans consider their past to be one of liberal freedoms, while China's post-war period was one of state control. These differences in starting points can lead to an entirely different debate taking place about where one should be going:

In the U.S. and Western Europe, the vast majority of individuals believe in representative democracy, civil liberties, and a market economy. Parties in these regimes differ on how best to achieve these goals, through more competition or more protection for instance, but the ideological debate does not question the validity of values such as democracy, rule of law, and civil liberties. In contrast, the appropriateness of democracy and individual liberties defines the ideological divide between conservatives and liberal in China.

Having agreed upon the liberal principles of "representative democracy, civil liberties, and a market economy" back during the time of the Enlightenment, people in the West today now debate exactly how such a liberal society should look. The Chinese people are still in the process of deciding whether or not they want a liberal society at all, a debate they haven't truly had in public since the New Culture Movement of the 1910s and 20s- nearly a century ago. In this way, Maoist China shared a critical similarity with Enlightenment Europe, despite the enormous differences between the two societies and the goals of their socioeconomic systems. Both were illiberal societies lacking both a capitalist market economy and political freedom. In both scenarios, liberals began to criticize the status quo and push for change in the system towards these goals, prompting conservatives to emerge and push back:

Deng’s market-oriented reforms and decentralization measures were opposed by Leftists, those who believed these measures would undermine the strength of the [Chinese Communist Party]. By bringing into China dangerous Western values, such as individualism and materialism, Leftists believed that Deng’s trajectory of economic reform would ultimately lead China to the fate of the USSR under Gorbachev (Wang 1997).

This is how we can now have people in China who are Maoist conservatives: those who wish to return to the "good ol' days" of socialism. That's why the study refers to the "'conservative' left": they are conservative in their desire for a return to the old status quo, but leftist in that said status quo is revolutionary socialism. We can see something similar in modern Russia, a nation which shares a similar past: many of today's self-identified "communists" like Gennady Zyuganov and the National Bolsheviks now also hold deeply nationalist and traditionalist views that are often associated with the far-right.

Farms and Cities

The results of the study only become more interesting. Though warning of potential sampling issues with their results, the authors report:

At the provincial level, we find that liberal ideology is highly correlated with modernization, measured by the level of economic development, trade openness, and urbanization. Coastal provinces (and municipalities) that are more economically developed... are much more liberal than poorer interior provinces... At the individual level, we find a strong positive relationship between liberal ideology and both education and income.

Foreign Policy Magazine takes their data and maps it, with the more "conservative" provinces being shaded red and the more "liberal" ones being shaded blue:

Part of this outcome is predictable. There's a large body of political science research suggesting that higher levels of education are associated with liberal positions on society and politics, such as having more "individualist values," having a "willingness to extend civil liberties to nonconformist groups," being less supportive of "ethnic exclusionism" and "chauvinism," and so on. But there are also economic reasons for this difference.

It's now cliché to point out that China has witnessed an "economic miracle" since economic liberalization. The number of people living on less than $2 a day has fallen to a quarter of what it was in 1990, and GDP per capita in U.S. dollars for the Chinese grew more than 59-fold from 1970 to 2013. There are many people who have benefited enormously from this economic growth, particularly those from coastal regions with the education and skills necessary to acquire high-wage jobs. It's no wonder that these are the people supporting liberalization, as they are the ones who have seen its benefits the most. Even political liberalization would benefit them the most, as they are more likely to have the education and connections necessary to become the people most actively involved in liberal democratic politics and pushing for their interests.

The benefits of this rise have not been shared equally, however. In 1981, the poorest fifth of Chinese citizens made 8.7 percent of national income. In 2010, their share fell to 4.7 percent. This is largely because of the neoliberal nature of the policies that China has implemented since Deng Xiaoping (critics of neoliberalism believe it inherently exacerbates inequality). Deng's reforms produced far more economic growth in coastal provinces and urban areas than in inland provinces and rural areas. Along with trade liberalization and privatization, policy also shifted towards providing benefits through tax-funded social welfare programs, instead of through collectivized farms and work units. For quite some time, the burden of that taxation disproportionately fell on farmers, who had to pay a regressive agricultural tax and a variety of fees while most urban workers were able to avoid paying any income tax up until the early 2000s. This set up was designed to encourage urban industry development. It succeeded, but at the expense of rural China. Policies have since changed (the agricultural tax was abolished in 2006, and China's "Di Bao" minimum income guarantee program was expanded to rural citizens the next year) but the contributions it made to inequality are still very apparent. One study looked at taxes and subsidies in 1988, 1995, and 2002 and found:

...distortions resulting from policies allowed urban households to escape most of the direct tax burden... [while] the rural population paid tax, although they received very little in terms of either private transfers or public services at the national or local level... these policies have contributed to the persistent and widening urban-rural gap.

This gap in economic conditions encourages the mass migration of rural workers to urban areas that China has been seeing for quite some time now. The percentage of Chinese people living in urban areas rose from 19 percent in 1980 to 54 percent in 2014, and the average rural population growth rate over the last five years is -2.1 percent. The changes brought about by this migration, in turn, disrupts everyday life for those who remain in rural areas. With both unstable social lives and dissatisfaction at the shift from Mao's pro-rural policies to modern pro-urban policies, it's easy to see why many rural Chinese would embrace Chinese conservatism, which promises both stability and a return to Maoist ideals. As Pan and Xu summarize:

Those who are relatively better off in China’s era of market reform tend to welcome additional

market liberalization as well as political reform toward Western models of democracy. Those

who are relatively worse off tend to oppose moves toward either economic or political reform.

The Future of China

While the ideological spectrum of China may seem odd and incoherent to us, it is perfectly logical in its structure. "Liberals," who tend to live in economically advanced coastal provinces, prefer free market economics, democracy, and cultural permissiveness. "Conservatives," who tend to live in more rural inland provinces, support state intervention in the economy, single-party rule, and traditional values. These two groups formed as a result of political, social, and economic conditions not entirely dissimilar to those of Enlightenment-era Europe, which spawned similar political camps.

Unlike Enlightenment Europe, however, China is not currently on a path of both economic and political liberalization, but, rather, only of economic liberalization. Is this sustainable? Evan Osnos points out that "without ideology, the legitimacy of the Chinese government rest[s] ever more on its satisfying and pleasing the public." With Chinese economic growth slowing, the role of the Chinese state may just be called into question. Only time will tell.

Thanks to Brett Bezio for help in editing.

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by

two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by  shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by

shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by  happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by

happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by  itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr

itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by

shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by  yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by

yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by  orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by

orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by  5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo

5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by

woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by  a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

women sitting on rock near body of waterPhoto by

women sitting on rock near body of waterPhoto by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by