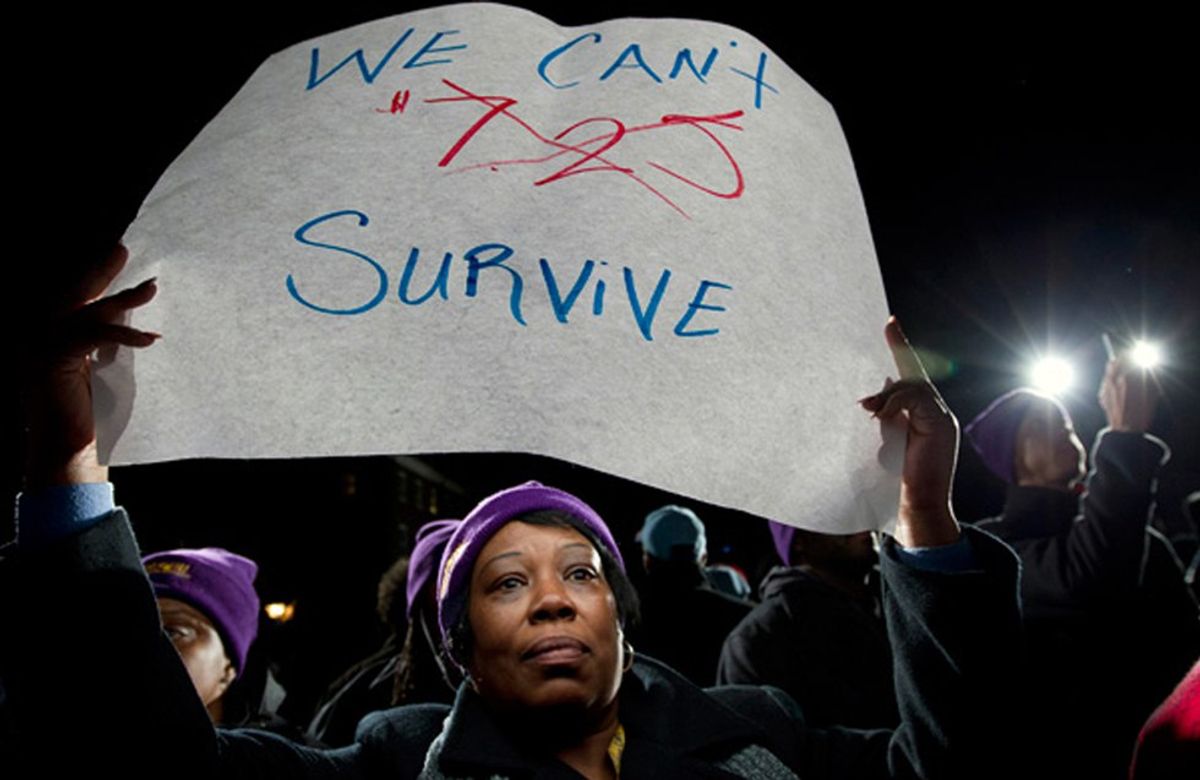

Last week, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo delivered a major victory to the workers who are fighting for a $15 minimum wage: he announced a $15 minimum wage for state employees. This victory came in the context of a broad movement of unions and workers fighting under the banner of "#FightFor15," pushing for a federal minimum wage hike of $15 over the next several years, more than double its current level of $7.25. Supporters, including Democratic Presidential Candidate Bernie Sanders, argue that the current minimum wage is far too low to provide workers with the amount of money neccesary to support themselves in even a basic way, while opponents argue that a $15 minimum wage has the possibility of doing serious damage to the economy in the form of higher unemployment.

They're both right. Every American absolutely deserves to earn a living wage, and the price of living is currently rising far faster than the wages of workers. But it's also true that, while moderate minimum wage hikes have no serious effect on unemployment rates, a raise to a $15 minimum wage might have much stronger effects. Certain cities might be able to handle such a wage hike, but many other areas probably won't. Fortunately, there's an alternative to a $15 minimum wage that handles both problems without the same potential negative effects as a $15 minimum wage.

Raising the Minimum Wage

Prices for critical goods have been increasing faster than the minimum wage has. Between January 2000 and January 2015, transportation has increased 28.7 percent, housing has increased 41.9 percent, the price of food and beverages has increased 47.7 percent, and medical care has increased 72.6 percent. Since 2000, the cost of tuition and fees for a four-year degree at a public college, which is often many people's only chance to get a better-paying job, 94.2 percent at public schools. Over the same period, the minimum wage has only increased 40.8 percent. In other words, many of the most basic needs for someone working a minimum wage job have been growing increasingly harder for them to acquire as time goes on, making the obvious case to raise the minimum wage and index it to inflation in some way.

Furthermore, most evidence suggests that the negative effects of a moderate raise in the minimum wage are insignificant. A 2013 meta-analysis looked at 64 different studies on the effects that raising the minimum wage has on employment and weighted their outcomes based on the methodological quality of the studies. The results? "...[W]e have reason to believe that if there is some adverse employment effect from minimum-wage raises, it must be of a small and policy-irrelevant magnitude." Economists Dale Belman and Paul J. Wolfson found similar results when they published their own meta-analysis in the book "What Does the Minimum Wage Do?", reviewing over 200 publications on the effects of the minimum wage. In the conclusion, they state that they found that "moderate increases in the minimum wage are a useful means of raising wages in the lower part of the wage distribution that has little or no effect on employment and hours." Economist John Schmitt wrote a comprehensive report explaining the reasons for this outcome.

A 2013 poll of a forum of Ivy League economists found that, even though concerns about unemployment were mixed, 49 percent of the respondents agreed that a $9 minimum wage indexed to inflation would “be a desirable policy" on net while only 11 percent disagreed. In 2014, a left-leaning think tank got more than 600 economists (including 7 Nobel Prize winners and 8 past presidents of the American Economic Association) to sign a letter in support of a bill in congress that would raise the minimum wage to $10.10 and index it to inflation.

Thus, there’s a fair amount of reason to support the idea that we should raise the minimum wage a moderate amount. However, there is obviously some point at which raising the minimum wage would result in the negative impacts outweighing the positive impacts; otherwise, we could just set a $1,000 minimum wage and make everyone a millionaire. Berman and Wolfson, the same economists who found no employment effects for moderate wage increases, also noted that they aren't sure whether the same outcome would hold true for "large increases," and that they suspect "that large increases could touch off the disemployment effects that are largely absent for moderate increases." Even Economist Thomas Piketty wrote in his recent best-seller on the recent history of economic inequality, "Capital in the Twenty-First Century":

Obviously, raising the minimum wage cannot continue indefinitely: as the minimum wage increases, the negative effects on the level of employment eventually win out. If the minimum wage were doubled or tripled, it would be surprising if the negative impact were not dominant.

No one knows where the point is at which the minimum wage would become a problem, but if we more than double our minimum wage to $15, we’re far more likely to find it. That’s because $15, when you adjust it for purchasing power, would effectively be the highest government-set minimum wage in the world. Though you often hear about high hourly minimum wages in other countries, none of them top Luxembourg’s $12.40 USD when you take the cost of living into account. Because of that, we don’t really have any solid idea what the effects of a $15 minimum wage would be. It would be entering unexplored territory, from a policy perspective.

Arindrajit Dube, one of the most-cited economists on the topic of the minimum wage and a signer of the pro-$10.10 minimum wage letter I mentioned above, said “[‘I’d be concerned’] if there were a $15 minimum wage in the restaurant industry… it might lead to the substitution of automation for workers.” Critics may overestimate the exact wage at which it will happen, but they're fundamentally right in saying that setting minimum wages too high would make automation a more cost-effective option than hiring workers for a number of industries. Regardless of whether its through reducing available hours or hiring less workers, a reduction in the demand for minimum wage labor would be a bad thing for workers filling or looking to fill those jobs. It's quite possible that such a loss would do more damage to working class America than the higher wages would benefit them.

As some of Dube’s work illustrates, it would be especially bad for workers in rural areas with lower costs of living, as the economies they live in would be less able to absorb a higher wage floor. This is especially bad, since rural areas have been experiencing a far slower job recovery than urban areas have. To take regional purchasing power into account, Dube has recommended state and local minimum wages set to half of the area’s median wage. Applying this formula would result in a minimum wage hike for every state in the nation, from a minimum wage of $7.97 in Mississippi to $12.45 in Massachusetts. No city in America would reach a $15 minimum wage under his standards, but a few like Washington D.C. and San Francisco would come close, which suggests that city-wide $15 minimum wage laws in such cities are interesting experiments that seem likely to succeed. Thus, $15 minimum wages in certain cities might work out quite well, but it's applying them federally that poses an issue.

Again, no one knows what the exact effects of a federal $15 minimum wage will be, but we do have reasons to believe that the net effects could be quite negative. The problem is that raising the minimum wage to just $10.10 an hour by itself still might not be enough to guarantee every American a living wage. That's why a $10 minimum wage should be accompanied by an additional policy: wage subsidies.

Wage Subsidies

Wage subsidies are essentially a government payment to workers to supplement the wages they receive. Say a $10 minimum wage is passed. You earn $10 an hour and work 160 hours in a month, meaning that you earn $1,600 that month. But then, the government creates a $5 per hour wage subsidy program for low-income workers. Additional revenue is generated through higher taxes on the wealthy, but your employer can now raise your wages by an additional $5 an hour and fully deduct the cost of doing so (plus a little extra) from their corporate tax bill. When they do so, you're now receiving a wage of $15 an hour, but $5 is effectively being paid for by the government.

Instead of eliminating jobs for low-income earners, which a $15 minimum wage could possibly do, this would create jobs for them. All businesses have to pay a taxes, but they can avoid part of that by instead hiring minimum wage workers and then paying them all $15 an hour. As Harvard Economist Lawrence Katz explains, "firms are likely to respond to wage subsidies by increasing their utilization of workers in the targeted population," i.e., hiring more low-wage workers. This both grants a $15 minimum wage for workers and makes it easier for them to find a job.

If you're a minimum wage worker already in a job, your boss has the choice of either paying you more or firing you when the minimum wage increases. As we've seen, your boss is extremely unlikely to fire you for a modest increase to $10.10 or so, but he would be more likely to do so for an increase to $15. With wage subsidies, however, your boss now has the choice of paying you more or paying their full tax bill. Because they would receive the cost of the wage increase from the government plus a small incentive bonus, raising your wages is now the cheaper of their options, not to mention the fact that higher wages means that you're likely to be more productive at work. Even if your boss turned down the program- literally spending his own business' money to make your life worse- other businesses will be more than happy to offer you a job so that they can reap the benefits.

When all is said in done, the end result is that you earn higher wages paid for by taxes on the wealthy. In terms of the distribution of wealth, this would be an even more progressive policy than raising the minimum wage, since the minimum wage is not incredibly effective at fighting inequality when it is not accompanied by the right policies. In "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," Thomas Piketty states that "the minimum wage has an impact at the bottom of the distribution but much less influence at the top, where other forces are at work." Wage subsidies, on the other hand, would tackle inequality much more directly.

The subsidy would need to phase out as income rises quickly enough that it doesn't end up subsidizing those earning a significant amount of money, but slowly enough so that it doesn't seriously discourage raises. This phase-out, properly balanced, would add an additional benefit: wage subsidies are far better targeted towards fighting poverty than the minimum wage. Even proponents of raising the minimum wage to $12 by 2020 acknowledge that a third of those who would benefit from it live in households that earn more than $60,000 a year. Raising the minimum wage would benefit millions of poor and working class Americans, of course, but wage subsidies as a policy help only them, making it a much more precise anti-poverty policy.

If a program like this became too large, of course, it would create problems. If businesses know that there employees will receive additional money through wage subsidies, what's to stop them from, as Blogger Kevin Drum puts it, "gaming the system and reducing wages because they know the wage subsidy will make up the difference?" This is a fair point: if you're already earning low wages at your job when this program comes into play, it is possible for your employer to just reduce your wages down and then collect the tax benefits of raising them again, leading to wasted tax revenues. But that's why combining a $10.10 minimum wage (indexed to inflation) and a wage subsidy program in tandem is the perfect way to guarantee a living wage: placing part of the direct burden for higher wages on employers and the rest on the government allows for us to reap the benefits of both approaches while minimizing the damages of both.

So, if wage subsidy programs could work so well, why don't we currently have any? Well, here's the good news: we actually do.

EITC

The government does currently have something similar to the wage subsidy program described above, and it's called the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC is different in a number of ways, however. When filing their taxes, low-income workers are eligible for the EITC, which reduces the amount they owe in taxes by a certain amount that depends on a variety of factors. Additionally, it's "refundable," meaning that workers who don't owe any taxes can still receive it in the form of a tax rebate: a check in the mail for the amount that they're eligible for.

There's a large body of research supporting how effective the EITC is in helping out low-income workers and their families, and it has found supporters in everyone from the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities to Republican Presidential Candidate Jeb Bush.

This option of cutting out the middle man and giving the money directly to workers seems like a superior option to wage subsidies, but there are a number of major drawbacks. First, placing the onus for redeeming the credit on employees makes it very easy for them to miss: in 2012, 20 percent of those who were eligible for the EITC didn't claim it. This is likely because of the absurd complexity of our tax code, but also possibly because many workers don't want to be seen as receiving a "government handout," something which is shamed in American culture. Noah Smith, professor of finance at Stony Brook University, points out that "wages are money that people feel like they have 'earned'," so an employer-based wage subsidy will be easier than the EITC for them to accept because "from the worker's perspective, it will just look like wages went up." For wage subsidies, the businesses (who sometimes can have their own accountants and tax specialists) are the ones who file the taxes, removing the hassle for workers and ensuring that they get the money in the form of wages.

Second, giving money to workers once a year in the form of a tax rebate makes planning much harder. When you're living check-to-check, long-term economic planning is very difficult, so workers have more to gain from just receiving their benefits with each check instead. Finally, the current structure of the EITC ties its benefits to things like marriage and how many children you have, leading to perverse incentives and a weak support for single, childless workers. A wage subsidy wouldn't have those problems.

The Hybrid Solution

The Brookings Institution proposed something similar to a wage subsidy-minimum wage hike policy early last year, arguing for a combination of a $10.10 minimum wage indexed to inflation and an expanded EITC:

Although past increases do not appear to have adversely affected employment, there is no denying the risk that much larger increases might pose to the least skilled workers. Raising the minimum from its current $7.25 to $15.00 per hour, as some have advocated, would… likely have some impact on hiring…

If we are really worried about families at the bottom, a better way to improve their lot is to increase the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) since it… will not significantly affect employers.

This is a good alternative to a $15 minimum wage, but it would be even better if we not just expanded the EITC, but turned it into a proper wage subsidy as well. The authors of that report estimate that their proposal "reduces the poverty rate by about 4 percent, lifting nearly 1.8 million people out of poverty," and it would surely help millions more near the poverty level. We can assume that the same policy with a wage subsidy in place of the EITC would do even more.

This is by no means an end to poverty in America. Indeed, ending poverty would require looking outside of employment altogether, since those children and the elderly (who can't work) make up more than half of those in poverty, and the number rises to more than two-thirds when you include the disabled (many of whom can't work much or at all). Additionally, this policy might come out to be quite expensive. However, this policy- raising the minimum wage to $10.10, indexing it to inflation, and then turning the EITC into a robust wage subsidy program- will provide a living wage for millions of Americans who are currently struggling to make ends meet without hurting the job market in the ways that a $15 minimum wage could, possibly even improving it instead.

people sitting on chair in front of computer

people sitting on chair in front of computer

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by

two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by  shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by

shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by  happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by

happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by  itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr

itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by

shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by  yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by

yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by  orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by

orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by  5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo

5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by

woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by  a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

women sitting on rock near body of waterPhoto by

women sitting on rock near body of waterPhoto by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by